Psychology

fromPsychology Today

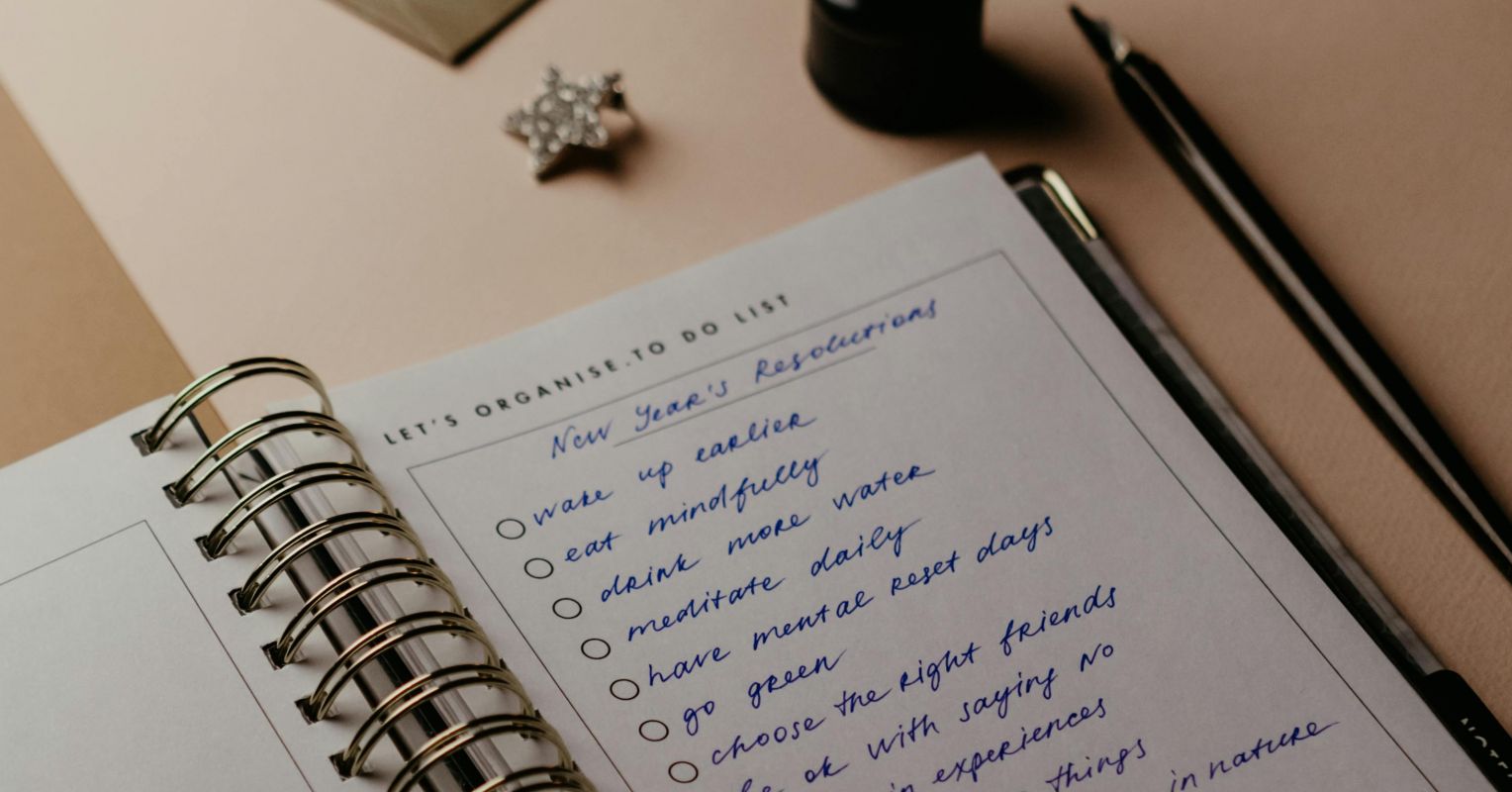

4 days agoWhy Behaviour Change Is So Hard to Do

Behavior change fails when immediate costs exceed rewards, not due to willpower; relationships unconsciously reinforce old behaviors while punishing new ones, and reinforcement proves more effective than punishment for lasting change.