#well-being

#well-being

[ follow ]

#mental-health #resilience #happiness #gratitude #positive-psychology #relationships #mindfulness #holiday-stress

fromwww.mediaite.com

2 days agoAmericans Optimism Drops To New Low Under Trump: Poll

A recent Gallup survey based on more than 20,000 interviews found Americans' optimism about their future personal lives has fallen to a new low. Gallup released findings this week from their National Health and Well-Being Index, which is based on data collected from thousands throughout the four quarters of the year. More than 22,000 interviews were spread across all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

US politics

fromEntrepreneur

3 days agoThese 5 Daily Habits Separate Top Leaders From Everyone Else

Leadership is often thought of as managing teams, strategies or organizations. But the truth is, leadership starts with managing yourself. A leader who lacks discipline in their personal life, whether in health, time or energy, will struggle to lead others with clarity and consistency. Without personal self-management, even the best leadership strategies fall apart. This is why self-discipline is often called the hidden foundation of leadership success.

Wellness

fromSilicon Canals

1 week agoIf you're happiest with just a few close friends instead of a large social circle, psychology says you probably have these 7 traits - Silicon Canals

Ever notice how some people seem to thrive at huge parties while you're mentally calculating the earliest acceptable time to leave? Or how your Instagram feed is full of group photos from weekend brunches with fifteen people, but the thought of coordinating that many schedules makes you want to take a nap?

Relationships

fromPsychology Today

1 week agoHow Can Patience Help You Deal With Life's Frustrations?

Patience is a capacity to endure difficulties, frustrations, and suffering with some sense of calm. Perseverance, self-regulation, and judgment are components of patience. Patience can help you manage your emotions, reactions, and responses in stressful situations. While positive psychologists don't specifically name patience as one of the top 24 character strengths, it is seen as an important element of human behavior. Strengths researchers propose that patience is an amalgam of several recognized character strengths, including perseverance, self-regulation, and judgment (Niemiec, 2018; Peterson and Seligman, 2004).

Mental health

fromBuzzFeed

1 week ago30 People Are Sharing Their Secret "Grandparent" Habits That Actually Make Life Way Better

Younger people definitely laugh (even lightheartedly!) at the things older people tend to do, like napping, playing bingo, or eating dinner early. But recently, the BuzzFeed Community wrote in to share the "old person" habits they've adopted that actually make life way better - and it got such a great response that even more people shared habits of their own! So, from young and old alike, here are some "old person" habits that you might consider adopting for yourself:

Wellness

Philosophy

fromThe Conversation

3 weeks agoIs being virtuous good for you - or just people around you? A study suggests traits like compassion may support your own well-being

Compassion, patience, and self-control often increase personal well-being by enhancing positive feelings and perceived meaning in everyday moments.

fromwww.theguardian.com

1 month agoThe secret to being happy in 2026? It's far, far simpler than you think

I have a proposal to make: 2026 should be the year that you spend more time doing what you want. The new year should be the moment we commit to dedicating more of our finite hours on the planet to things we genuinely, deeply enjoy doing to the activities that seize our interest, and that make us feel vibrantly alive.

Wellness

fromPsychology Today

1 month agoWhere in Your Body Do You Live?

When an event, such as the death of someone close, affects you in a major way, a common idiom says the event "really hits you where you live." But where, exactly, do you live? Not in a country, state, city, house, or apartment, but inside your body? Until recently, I assumed everyone was like me, localizing "self" inside the head.

Psychology

fromThe Atlantic

1 month agoHow to Follow the Right Star

A much-loved Christmas story tells about the journey of the Magi-the three Wise Men who came seeking the baby Jesus in Bethlehem. "Where is He who has been born King of the Jews?" they ask. "For we have seen His star in the East and have come to worship Him." The essence of the tale is their unshakable faith in a worldly sign-a star in the sky-which the Magi trusted would guide them to the savior of the world.

Mental health

fromPsychology Today

1 month agoHow to Give the Best Gifts

If someone truly wants an object, consider choosing one that's fair-trade and environmentally responsible. Sadly, much of the "stuff" we find on shelves has been made in sweatshops by underpaid workers (and even children). You can make a difference by being selective about where you spend your dollars. Ethical consumption increases well-being-not just for the recipient, but for the giver, too-because it aligns our actions with our values and our care for the larger world.

Wellness

fromPsychology Today

2 months ago6 Success Strategies for Aging Well

The view that aging is all downhill may be one that you implicitly believe in. How many times have you made jokes about your age, made jokes about someone else's age, or just looked in the mirror with despair at the toll time takes on your face? Yet, the media is full of images of people whose aging brings them joy rather than pain.

Public health

fromLos Angeles Times

2 months agoDua Lipa's choreographer invites you to wiggle, hum and let your inner child loose

On a Tuesday night in Atwater Village, Teresa "Toogie" Barcelo is creating a portal. With her arms stretched out, she beckons the participants of her movement workshop, Wiggle Room, to join her on the other side, where they will meet a renewed version of themselves. "Walk into the next iteration of yourself," she commands. The participants, who have spent the last hour squirming, shaking and humming, cross the invisible threshold. Their limbs swing loosely, their smiling faces sticky with sweat.

Wellness

fromPsychology Today

3 months agoHow Purpose Envy Misleads Us

Envy arises when we compare ourselves to someone else and conclude they're better off. We've all been there. And while envy is a universal emotion, it's also a corrosive one. In a large longitudinal study of more than 18,000 adults, researchers found that higher levels of envy predicted poorer well-being years later. Put simply: The more envious we are, the worse we tend to feel over time.

Psychology

fromPsychology Today

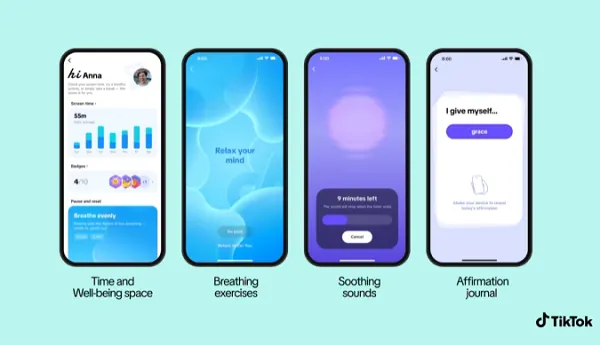

3 months agoThe Science Behind Self-Affirmations

A large meta-analysis pooling data from 129 independent tests across 67 published studies with over 17,700 participants found that self-affirmation produces significant, albeit modest, improvements in multiple aspects of well-being. These include stronger self-perception, enhanced general and social well-being, and reduced psychological barriers like anxiety and negative mood (Zhang, Chen, and Wang, 2025). And, these benefits are not fleeting; follow-up tests showed that long-term effects, especially in reducing psychological obstacles, were sometimes even stronger than immediate outcomes.

Mental health

fromBusiness Insider

3 months agoI tracked my moods every day for almost 5 years. One habit skyrocketed my happiness.

For almost five years, I've been dutifully drawing little green dots at the top of my journal entries. A small green dot means it was a generally good day, a slightly bigger one that it was pretty fantastic. A huge one represents one of the handful of no-notes, absolutely perfect days of the year. Orange dots equal stress, red denotes anger, and blue means feeling blue.

Psychology

fromThe Local Germany

3 months agoWho are the happiest immigrants in Germany?

Lead researcher Professor Katharina Spiess and her team questioned 30,000 people in Germany aged 20 to 52 for the study, focusing on both newcomers and those with deeper roots in the country. It asked each respondent to rate how "satisfied" they were with their life currently on a scale of 0 to 10. The aim, according to BiB, is to use well-being as a measure not only of personal happiness but also of social integration and economic prosperity.

Germany news

fromwww.scientificamerican.com

3 months agoThe Neuroscience behind the Parenting Paradox' of Happiness

But one of the simplest, most personal considerations is whether, and how, having a child will affect a person's quality of life. Here, psychologists studying well-being have encountered what's sometimes called the parenting paradox: parents report lower mood and more stress and depression in their daily lives than adults without children; yet parents also tend to report higher life satisfaction in general.

Parenting

fromThe Atlantic

3 months agoYes, Money Can Make You Happier

Many stressed-out people are attracted to eastern meditation, believing that it will give them relief from their "monkey mind" and lower their anxiety about life. Unfortunately, the monkey usually wins because people find the mental focus required for meditation devilishly hard. On a trip last year to India, I asked a Buddhist teacher why Westerners struggle so much with the practice. "You won't get the benefit from meditation," he said, "as long as you are meditating to get the benefit."

Mindfulness

fromBig Think

3 months ago5 ways immersion in art can boost your work-life happiness

and I demonstrate how art can gently tip the scales back toward harmony. Think of visual art as a toolkit to soothe the mind and spirit. Every day, we are inundated with imagery urging us to work harder, buy more ... and never stop. Art offers the exact opposite. It slows and calms us down, sharpens our critical thinking, nurtures happiness, and helps us resist the endless cycle of consumption.

Mental health

fromPsychology Today

4 months agoRevisiting the Feels: Why Nostalgia Is Good for the Soul

The concert was a collective exercise in nostalgia - that powerful emotion triggered by the intersection of experience and memory. Some people think of nostalgia as a sort of bittersweet feeling, an aching reminder of what we have lost. It is joy tinged with sadness, but primarily a positive emotion that is part of the human experience. It is a feeling that sneaks up on you, and not just at massive concerts.

Mental health

[ Load more ]