#emotional-regulation

#emotional-regulation

[ follow ]

#parenting #mindfulness #resilience #boundaries #leadership #anger-management #child-development #mental-health

Psychology

fromSilicon Canals

30 minutes agoPsychology says people who can spend an entire weekend without speaking to anyone usually have these 7 mental strengths others lack - Silicon Canals

People comfortable spending extended time alone possess psychological strengths including emotional self-regulation, self-sufficiency, and mental maturity rather than antisocial tendencies or damage.

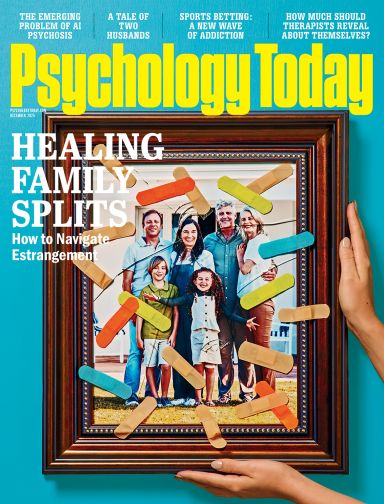

fromPsychology Today

6 days agoBeyond Positive Thinking

As Americans feel increasingly pessimistic about the future, the pressure to "stay positive" has never been more intense-or misplaced. Psychology has long shown that suppressing difficult emotions does not make them disappear. It makes the nervous system more reactive. When sadness, fear, and anger are treated as problems to eliminate rather than signals to understand, the brain remains on high alert. This is one reason forced positivity so often backfires, amplifying anxiety rather than easing it.

Mental health

Mindfulness

fromSilicon Canals

1 week ago8 quiet behaviors that reveal someone has done deep inner work even if they never talk about it - Silicon Canals

Deep inner work shows through subtle, consistent behaviors like pausing before responding and holding space without fixing, reflecting emotional discipline and cultivated wisdom.

fromPsychology Today

1 week agoWhat to Do When Your Feelings Are Too Big

For many people, feelings can get intense and out of control very quickly. While our feelings are always important and meaningful, our responses to whatever provoked the feelings aren't always responses that are in our best interests. By learning how to self-calm in the moment, you might spare yourself the unwanted consequences of acting too quickly when provoked. The process of managing our emotional responses so that we can return to a state of calm and make our best decisions is called emotional regulation.

Mindfulness

fromSilicon Canals

1 week agoIf you were the child who always had to keep the peace between your Boomer parents, psychology says you probably display these 8 rare traits today - Silicon Canals

Growing up, I became an expert at reading the room before I even knew what that meant. When my parents' voices would rise from the kitchen, I'd already be mentally preparing my peacekeeping strategy. Should I crack a joke to break the tension? Distract them with a question about homework? Or maybe just quietly start doing the dishes to remind them I was there? By the time they divorced when I was twelve, I'd spent years perfecting the art of emotional regulation.

Mental health

fromPsychology Today

2 weeks agoHow to Help Your Child When They Are Withdrawn and Moody

Teens can retreat into themselves when they find themselves confronted by difficult emotional circumstances. At times it is important and constructive to leave them to themselves as they adjust to these challenges. Parents often find it emotionally troubling to watch as their child has difficulty and want to fix things. It is important for the development of independence that a child be left to learn how to work things out.

Mental health

fromApartment Therapy

2 weeks ago46 Morning Journaling Prompts to Transform Your Mindset (It Only Takes 5 Minutes!)

We live in a fast-paced world that glorifies productivity. That often means prioritizing work ahead of your mental health or even your personal life. There's a constant push to do more, achieve more, and get it done more quickly - and the clock starts ticking the moment you wake up. It's hard to break free from this mindset and put yourself first, often leading to burnout. Enter morning journaling.

Mindfulness

fromSilicon Canals

2 weeks agoRewatching the same show over and over is your brain's way of coping with this - Silicon Canals

Last week, I caught myself starting The Office for what must be the fifteenth time. My partner walked in, saw Jim pranking Dwight with the stapler in Jell-O, and just shook his head. "Again?" he asked. And honestly? I couldn't explain why I kept going back to the same show when there's literally endless content available at my fingertips. But here's the thing: I'm not alone in this.

Television

Parenting

fromSilicon Canals

3 weeks agoThe nightly habit that could improve your child's behavior and emotional control - Silicon Canals

Consistent, predictable bedtime routines improve children's emotional regulation, behavior, and stress response by creating safety and stabilizing sleep-wake patterns.

fromPsychology Today

3 weeks agoEmotional Intelligence Is More Than Just Empathy

Emotional intelligence is all the rage and, many would argue, it has been for some time. Ask any psychology professor and they'll likely tell you that it's one of their students' favorite topics. There's certainly no question that it's incredibly necessary and relevant today. Given consistent psychological findings that humans desire to avoid suffering, emotional intelligence is what we all want in our partners, our friends, our colleagues, and... the world.

Psychology

Mental health

fromSilicon Canals

3 weeks agoPeople who were constantly told they were "too much" as children now display these 8 behaviors in every adult relationship without realizing they're still apologizing for existing - Silicon Canals

Childhood labeling as 'too much' leads adults to minimize themselves, causing anxiety, apologizing for existence, and submissive behaviors in relationships.

Mindfulness

fromSilicon Canals

3 weeks agoPsychology says if you can sit in silence without reaching for your phone, you possess these 8 rare qualities - Silicon Canals

Comfort with sitting silently without using a phone reflects strong emotional regulation and rare psychological strengths in a hyper-connected society.

fromPsychology Today

3 weeks ago3 Tell-Tale Signs of Invisible Growth

Some of the most meaningful forms of growth an individual can experience happen beneath their conscious awareness. Typically, it registers first as discomfort, ambiguity, or even a sense of regression. When growth is happening at a person's core level, they're likely to underestimate it or misinterpret it entirely. As a psychologist, I often see individuals who assume they're "stuck" precisely when some of the most important internal shifts are underway. This is because the mind rarely announces these changes with clarity.

Mental health

fromPsychology Today

4 weeks agoWhat Happens When We Are Triggered

Someone says something to us, and we are suddenly struck with a sinking feeling in our stomach. Someone does something, and instantly we become enraged or alarmed. Someone comes at us with a certain attitude, and we go to pieces. We hear mention of a person, place, or thing that is associated with an unresolved issue or a past trauma, and we immediately feel ourselves seize up with sadness, anger, fear, or shame.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness

fromABC7 Los Angeles

4 weeks agoGrogu heads to classrooms, living rooms in special Disney/LucasFilm collaboration with GoNoodle

Disney, Lucasfilm and GoNoodle released Star Wars-themed videos featuring Grogu to teach breathing, movement, mindfulness, focus, and emotional regulation for children.

fromPsychology Today

1 month agoThe Quiet Power of Coherence

A child was struggling to breathe after surgery. Monitors beeped erratically, staff spoke in rushed fragments, and fear hung in the air so thick it felt like fog. The mother stood frozen in shock. A nurse-one of those rare people who radiates groundedness-walked in. She didn't speak at first. She simply approached the mother, placed a gentle hand on her shoulder, and breathed slowly, visibly, intentionally.

Mindfulness

fromInsideHook

1 month agoA Nasty Phone Habit We All Need to Retire This Year

You can find them anywhere there are people and inclines: train platforms, gyms, grocery stores. They come in different shapes and sizes, they represent every age and demographic, but they all move in the exact same way - slow-motion shuffle, scroll, lift foot, poke screen, land foot, repeat. The worst ones get to the top (or bottom) of the stairs and suddenly stop. This would be justifiable if they received notification of a nuclear warhead careening towards the city. But it's usually just a Slack they have to read extra carefully.

Digital life

fromPsychology Today

1 month agoWhen to Leave a Relationship

Knowing when to leave a relationship is not a dramatic moment of collapse. More often, it is a quiet reckoning. A slow accumulation of truth. People imagine that leaving happens because love disappears or conflict explodes. In reality, many people leave because the daily effort of holding themselves together inside the relationship becomes weightier than the fear of being alone.

Relationships

fromBustle

1 month agoHere's Your Horoscope For Tuesday, January 13

A grounding connection forms between the moon in seductive Scorpio and Venus in committed Capricorn, setting a serious tone to your morning. Living up to promises, especially those made with a loved one, is non-negotiable. The moon's eclectic opposition to disruptive Uranus throws a wrench in your afternoon plans. However, Saturn's steady support of the moon is a reminder to stay in control of your emotional reactions, even when the unexpected occurs.

Relationships

fromPsychology Today

1 month agoWhy Do I Feel Lonely With People I Love?

He said it is not always about bright colors. Dark and grey tones can give an image more depth and strength than bright colors ever could. Also, it can show the rawness of a story and make it more powerful. I was not convinced. I even took a picture of the painting, thinking I would look at it again later. And it took me years to understand.

Mental health

fromPsychology Today

1 month agoStrengthen Your Mind the Way You Strengthen Your Body

Every January, millions of us set goals that promise control: eat better, exercise more, stress less. Yet the most transformative resolution may not be about controlling life-it's about expanding our capacity to engage with it. Stress isn't something to eliminate-it's something to train for. Just as we lift weights to strengthen our bodies, we can stretch our emotional tolerance to strengthen our minds.

Mental health

fromPsychology Today

1 month agoThe Wardrobe Reset and Emotional Alignment

January invites reinvention. Gym memberships spike, planners sell out, and wardrobes quietly become sites of negotiation. Who am I now? Who am I becoming? And what no longer fits emotionally as much as physically? While New Year resets often focus on productivity or discipline, clothing is one of the most overlooked psychological tools for change. What we wear is not superficial.

Fashion & style

fromPsychology Today

2 months agoWhy Some People Sound Calm When They're Not

In many collectivistic cultures, emotion is not experienced as purely personal. It is relational. Collectivistic cultures emphasise interdependence, social harmony, and the primacy of group well-being over individual autonomy. People tend to define themselves through relationships, roles, and obligations, and regulate their emotions in ways that maintain cohesion and respect within the in-group. Emotional expression is often moderated to preserve dignity, avoid burdening others, and protect relational stability.

Psychology

fromPsychology Today

2 months agoDistance and Destruction: The Forces Driving Conflicts

Most couples believe their recurring conflicts revolve around the issue at hand-what was said, what was forgotten, what should have happened differently. But in our work as clinicians, and in our own relationship, we've learned that it's not only the content of the conflict that matters. How partners respond to the conflict plays an equally important role in how quickly-and how well-they recover.

Relationships

fromPsychology Today

2 months agoThe Role of Journaling in Grief and Recovery

Grief doesn't follow a script. Whether you've lost someone suddenly or are navigating the slow unraveling that follows a major life change, it can be hard to find space for your emotions, let alone make sense of them. That's where journaling comes in. This commonly therapist-recommended tool has been shown to ease stress, clarify emotions, and support long-term healing. And, no, it doesn't have to be done daily to make a difference.

Mental health

fromPsychology Today

2 months agoUsing Bedtime Stories to Create Healthy Narratives in Kids

Reading your child a bedtime story-or making one up yourself-has so many benefits, but there's one that is often overlooked: Bedtime stories create powerful narratives in your child that you choose. (For more on narratives and why they're crucial for parents to know about, see this post.) How stories become narratives Children's stories affect kids on an emotional level. For instance, let's take the common absent-parent-returns-home story.

Books

Parenting

fromPsychology Today

2 months agoIs Your Teen Ready to Leave for College?

Emotional and social readiness—especially emotional regulation, frustration tolerance, autonomy, friendship skills, and parental willingness to let go—often outweigh academic readiness for successful college transition.

fromPsychology Today

2 months agoSurrounded by Leftover Holiday Food and Feelings?

In the days leading up to the event, we scramble to keep up with our daily obligations while preparing food, decorating, and traveling. The day itself often flies by, leaving us exhausted and hopefully content. But the day after the holiday can be a letdown. If we enjoyed the festivities, we have to wait another year to repeat the event. When things don't go well, we grapple with disappointment or other complex feelings.

Mindfulness

[ Load more ]