fromPinkNews | Latest lesbian, gay, bi and trans news | LGBTQ+ news

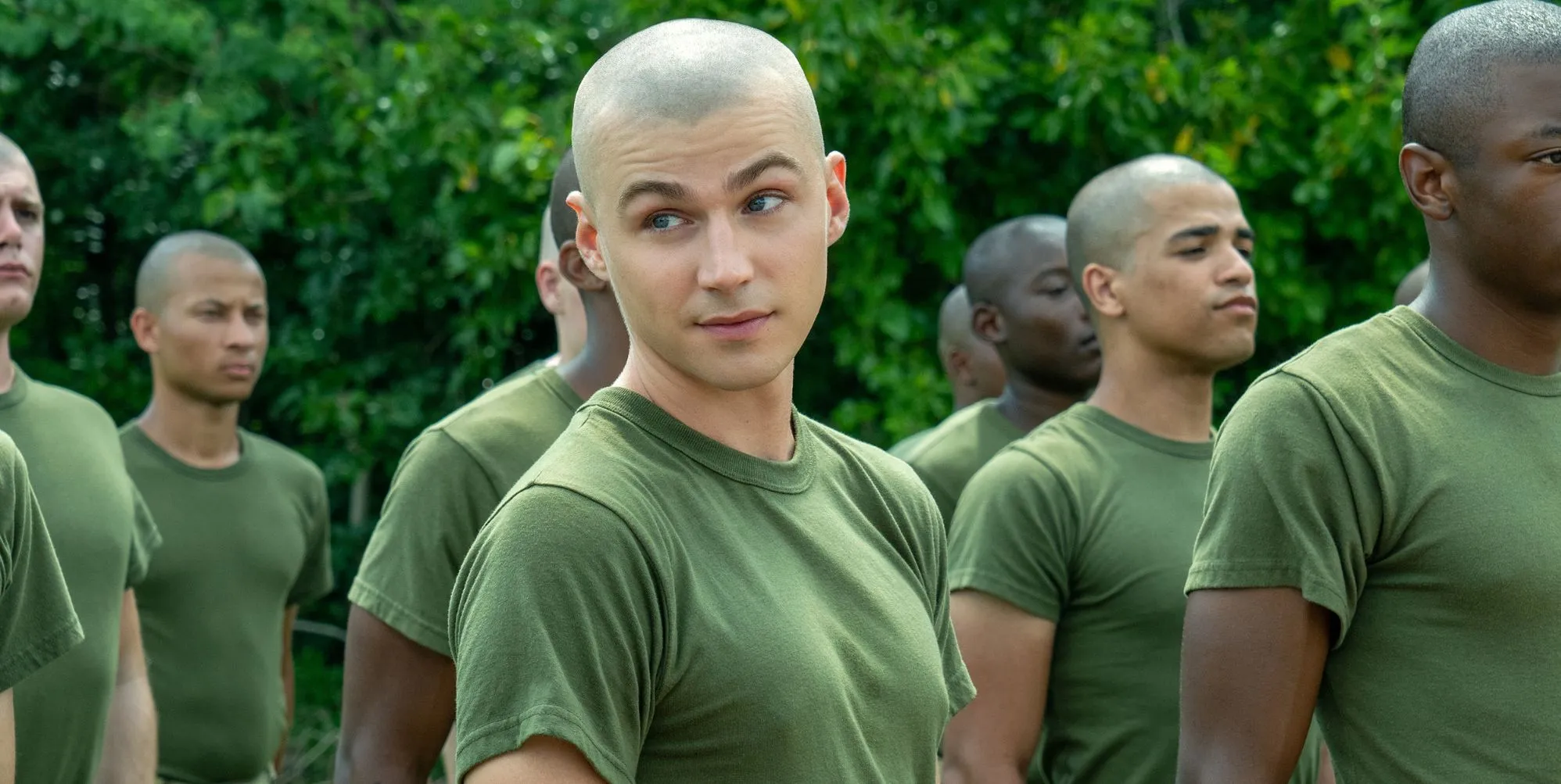

1 month agoEverything we know about The Body, Netflix's 'raunchy' new psychodrama

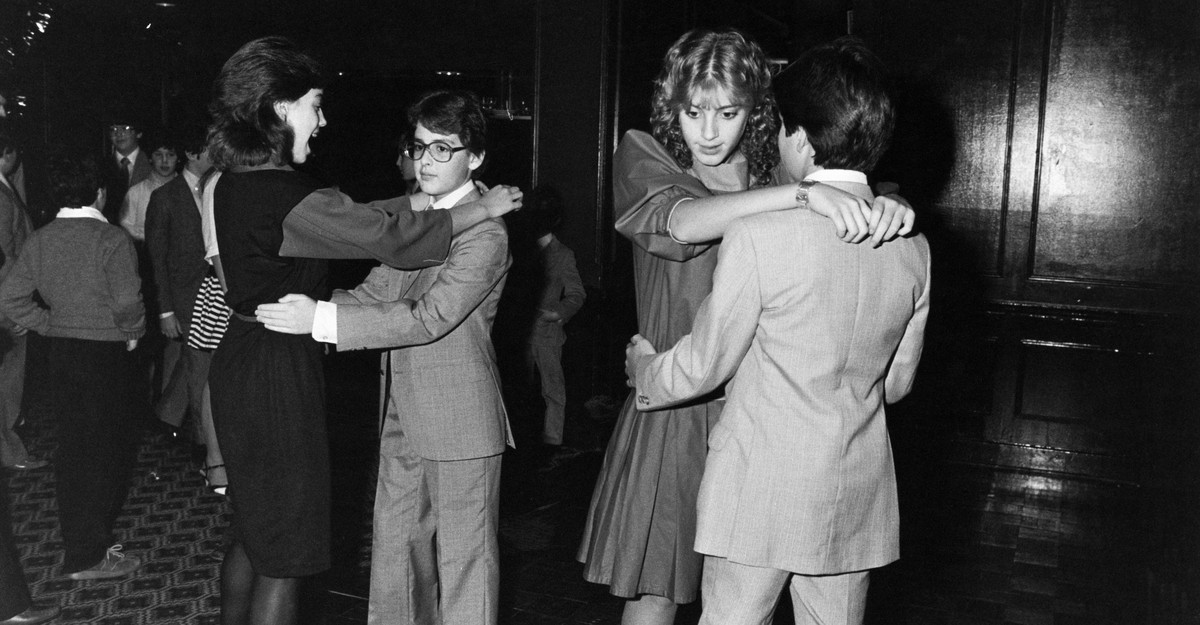

What do you get when you cross an all-women dance troupe with a rebellion against Catholicism and erotic '90s thrillers? Something supremely queer, I hope. In the words of Ayo Edebri: I'm simply too seated. This is The Body, a new Netflix psychodrama from queer writer-director and Blame actress Quinn Shephard, starring none other than The Traitors ' sapphic supreme, Gabby Windey (plus a host of other very talented stars) Announced back in October, the eight-part show is set to further the fascination with "raunchy" coming-of-age, sports-ish series when it's released later this year, and with a wink-wink-nudge-nudge approach to religion, too.