fromAnOther

4 hours agoMadeleine Dunnigan's Jean Is a Skilful Character Study in Teenage Angst

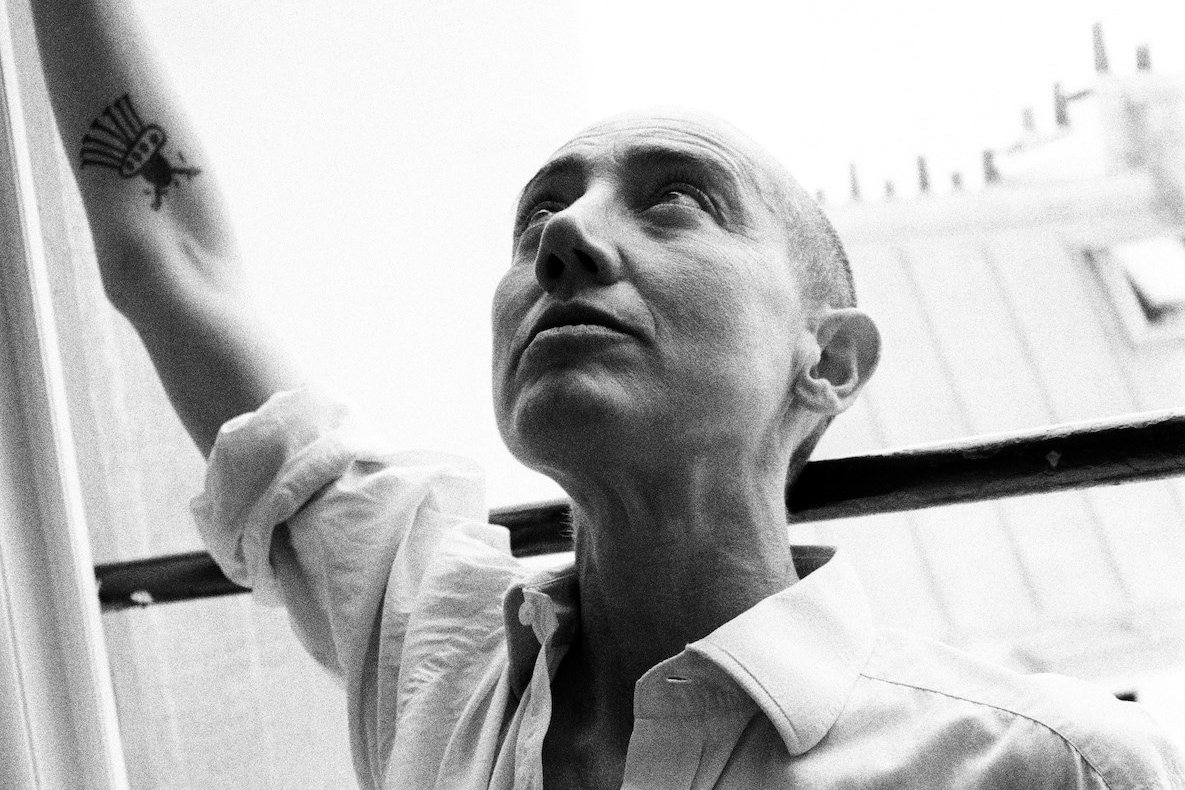

Jean is, in the words of its author, a novel about "alienation, told from the inside out". Set at a reform school over the sweltering summer of 1976, the heat rises as Jean fights (and fucks) the other boys, conflict and desire coalescing until the novel reaches its conclusion: his decision to walk out of his life for good. Dunnigan explores the ethics of early sexual experiences, British class dynamics and the crushing weight of - particularly masculine - conformity.

Books