#film-adaptation

#film-adaptation

[ follow ]

#wuthering-heights #emerald-fennell #casting-controversy #emily-bronte #critical-reception #science-fiction

#science-fiction

Books

fromScary Mommy

4 days agoRyan Gosling Says 'Project Hail Mary' Is The Kind Of Movie He Wants His Kids To Grow Up With

Project Hail Mary is a sci-fi film about space survival that combines grand scale with intimate human storytelling, emphasizing hope and the capacity for extraordinary achievement through collaboration.

Film

from48 hills

4 days agoA Holocaust survivor in San Rafael finds his voice in 'The Optimist' - 48 hills

Herbert Heller, a Holocaust survivor who ran a children's store for 53 years, kept his survival secret for decades before becoming a sought-after speaker, inspiring a drama film directed by Finn Taylor.

Film

fromwww.theguardian.com

1 week agoWhat's under my saucepans? Rage!' Claire Foy, Andrew Garfield and cast on the set of The Magic Faraway Tree

The Magic Faraway Tree film adaptation brings Enid Blyton's beloved magical landscapes to life with elaborate sets featuring edible environments and fantastical creatures, starring 13-year-old Billie Gadsdon.

fromwww.npr.org

1 week ago'Hamnet' star Jessie Buckley looks for the 'shadowy bits' of her characters

What Maggie O'Farrell so brilliantly did, not just with Agnes and Shakespeare's wife, but also with Hamnet, their son, was to bring these people ... and give them status beside this great man. ... [And] give the full landscape of what it is to be a woman.

Arts

Film

fromThe Nation

1 week agoThe Bad Vibes of "Wuthering Heights"

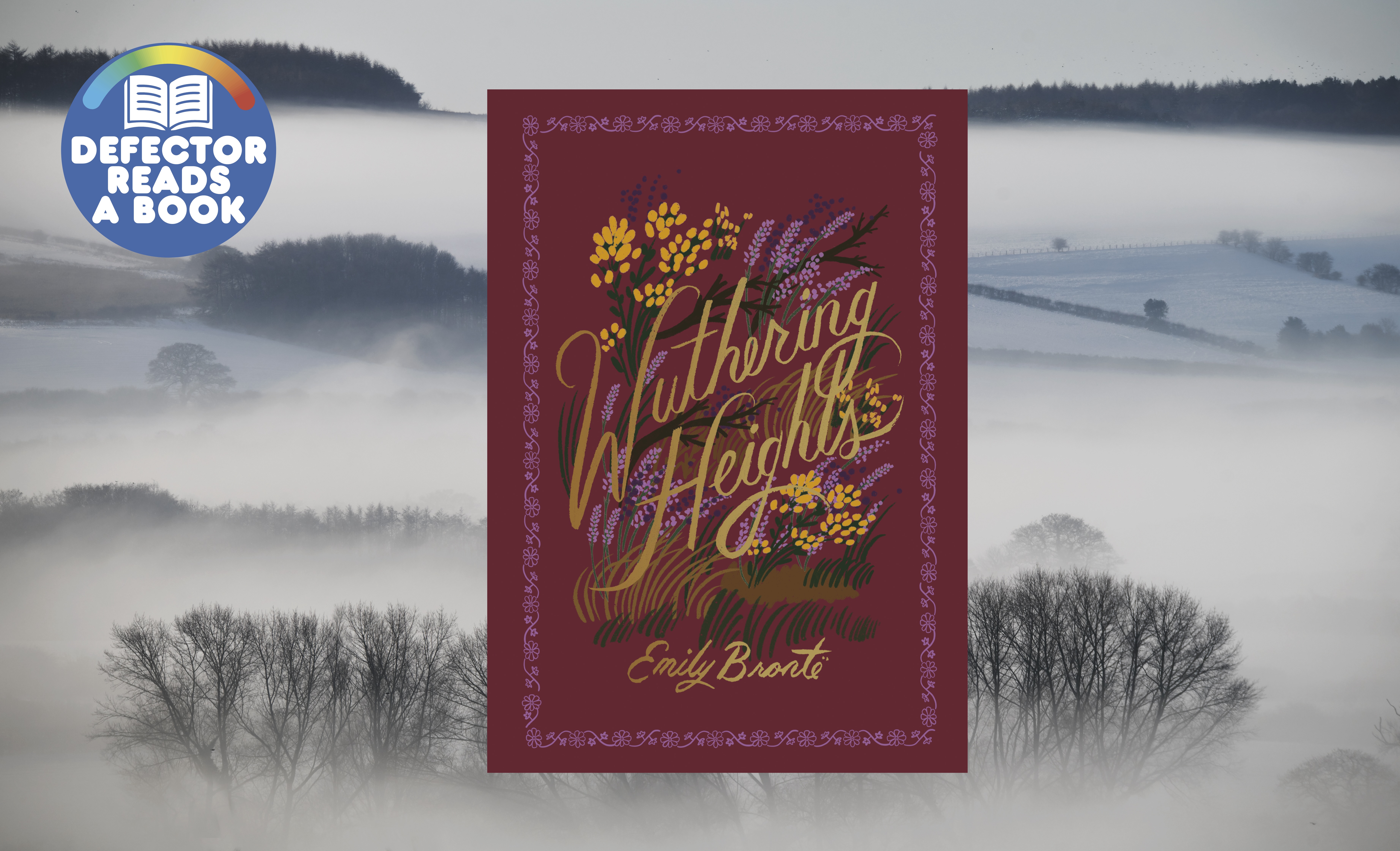

Emerald Fennell's Wuthering Heights prioritizes contemporary aesthetic over literary faithfulness, reducing Brontë's complex novel to a shallow love story that reflects modern short attention spans rather than engaging with the source material's depth.

fromwww.theguardian.com

2 weeks agoOne Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest reviewed archive, 1976

Taken from a widely read novel by Ken Kesey, it is a prime example of how a subject which must have looked destined for the cultural ghetto of the art circuit can be hoist by its bootstraps into the commercial field and festooned with Oscar nominations. You can do this of course only by making compromises by engaging a star with redoubtable box office muscle by jollying your audience along a little before the real crunch comes.

Film

fromwww.theguardian.com

2 weeks agoAll You Need is Kill review time loop anime offers giant alien flower for Groundhog Day with mechs

The second film adaptation of Hiroshi Sakurazaka's 2004 eponymous novel, this new one is considerably inferior to Edge of Tomorrow from 2014, Tom Cruise's own Groundhog D1ay with mechs. It's not a question of budget or aesthetics simply a gaping hole of engaging characterisation and inner spark that makes this time loop a grinding chore, rather than a thrilling jailbreak from eternal recurrence.

Film

fromwww.theguardian.com

3 weeks agoThe Hunt for Gollum looks like a step too far for the endless Lord of the Rings franchise

Now in his 80s, Ian McKellen appears to have taken a strategically sedentary route for his appearance as Gandalf the Grey in the next year's Lord of the Rings weird-quel The Hunt for Gollum. You've probably heard about this thing: it's the new movie that's based on bits and pieces of JRR Tolkien's esteemed high-fantasy epic that were only mentioned in passing during the three original three-hour movies, and didn't get much more of a mention in the extended cuts that came out later.

Film

fromThe New Yorker

3 weeks agoDoes "Wuthering Heights" Herald the Revival of the Film Romance?

The important thing about adaptations isn't what's taken out but what's put in. Emerald Fennell's "Wuthering Heights"-or, as she'd have it, " 'Wuthering Heights,' " complete with scare quotes-is the season's second Frankenstein movie, because Fennell takes bits and pieces from Emily Brontë's novel and, adding much of her own imagining, reassembles them into a misbegotten thing that wants only to be loved. And paying audiences seem to love it, even if many critics don't.

Film

fromwww.theguardian.com

4 weeks agoIs Jacob Elordi really what Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights should look like? | Dave Schilling

This weekend brings the wide release of Saltburn director Emerald Fennell's adaptation of Emily Bronte's Wuthering Heights. As is befitting Fennell's established style, the movie offers over-the-top sexual titillation (though, crucially, zero nudity) and elaborate production design. Plus, a contemporary pop soundtrack from Charli xcx. A horny film version of a 19th-century novel is as adult-skewing as it gets at the box office these days.

Film

Books

fromenglish.elpais.com

4 weeks agoIs Heathcliff a narcissist, a madman, a proto-Marxist? The enduring enigma of the Wuthering Heights' hero

Heathcliff embodies a complex, contradictory cultural icon whose interpretations shift with eras, amplified by a new film adaptation starring Margot Robbie and Jacob Elordi.

fromArchitectural Digest

1 month agoAn Exclusive First Look at the Surreal, Symbolism-Packed Sets of Wuthering Heights

In Emily Brontë's 1847 novel Wuthering Heights, the moors of Yorkshire are wet with rain, fog-and symbolism. The rugged landscape separating the titular home from the neighboring estate, Thrushcross Grange, represents danger and harshness, but also a kind of wild freedom for the star-crossed lovers Catherine and Heathcliff, who explore the land together in childhood and spend their adult lives yearning for each other.

Film

Humor

fromIndependent

1 month ago'I just poured out all this stuff about getting divorced': John Bishop on saving his marriage - and how it became a Hollywood movie

John Bishop's first open-mic joke in 2000 launched his stand-up career and played a pivotal role in saving his marriage while inspiring a film.

fromConde Nast Traveler

1 month agoWhere Was People We Meet on Vacation Filmed?

"Number one for me was not faking too much," Haley says. "Obviously you have to fake stuff and you have to pretend you're somewhere where you're not. But I wanted this film to be grounded and believable, and for it to feel like you were actually on vacation with Poppy and Alex. So it was important to me to shoot it with our boots on the ground."

Film

LGBT

fromPinkNews | Latest lesbian, gay, bi and trans news | LGBTQ+ news

1 month agoMatt Damon reveals he and Ben Affleck almost starred in gay baseball film

Matt Damon and Ben Affleck nearly adapted Peter Lefcourt's novel The Dreyfus Affair into a gay baseball film, but the script was not strong enough.

fromThe New Yorker

1 month ago"The Chronology of Water" Is an Extraordinary Directorial Debut

"I remember things in retinal flashes," Yuknavitch explains in the book. "Without order." In another passage, she says, "All the events of my life swim in and out between each other," adding that, although her memory is nonlinear, "we can put it into lines to narrativize over fear." The liberation of time is central to modern cinema, because, once a movie is acknowledged as a work of first-person art as much as a book is, subjectivity itself becomes its overarching subject.

Film

fromVulture

1 month agoColleen Hoover Insists Her New Book Isn't About Herself

Out today, Woman Down centers on writer Petra Rose, an author who has writer's block and checks into a remote cabin to finish her next book. Petra, who took a hiatus after fans blamed her for a producer's decision to cut a fan-favorite character out of the film adaptation of her book A Terrible Thing, has "learned the hard way what happens when the internet turns on you," a synopsis states.

Books

fromHyperallergic

2 months agoThere's More to Look at Than Learn in 100 Nights of Hero

She constructed "Early Earth," the setting of two of her graphic novels, The Encyclopedia of Early Earth (2013) and The One Hundred Nights of Hero (2016). The former is a collection of creation myths for Early Earth, while the other is modeled on One Thousand and One Nights and its frame story of a woman delaying a man's predation by distracting him with storytelling.

Arts

[ Load more ]