#us-intervention

#us-intervention

[ follow ]

#venezuela #nicolas-maduro #delcy-rodriguez #international-law #chavismo #protests #maria-corina-machado

fromwww.aljazeera.com

2 weeks agoHaiti's transitional council hands power to US-backed prime minister

Move comes after council tried to oust PM Fils-Aime and the US recently deployed warship to waters near Haiti's capital. Haiti's Transitional Presidential Council has handed power to US-backed Prime Minister Alix Didier Fils-Aime after almost two years of tumultuous governance marked by rampant gang violence that has left thousands dead. The transfer of power between the nine-member transitional council and 54-year-old businessman Fils-Aime took place on Saturday under tight security, given Haiti's unstable political climate.

World news

fromwww.aljazeera.com

3 weeks agoExiled Venezuelans dream of returning home. What's stopping them?

For years, Luis Peche, a 31-year-old political consultant, dreamed of a Venezuela without its leader, Nicolas Maduro. Living under Maduro's rule, Peche saw friends flee the country for fear of hunger and repression. Others were imprisoned for their activism. Then, in May 2025, Peche himself was forced into exile after being tipped off that security forces were preparing to arrest him. He has lived in Colombia ever since.

World news

fromThe Nation

3 weeks agoReport From the Progressive International's Nuestra Summit

"Don't go!" more than one voice could be heard shouting in the packed Teatro Colón on January 24. The plea was in response to Colombian senator María José Pizarro Rodríguez's declaration that Colombia's President Gustavo Petro would be traveling to the White House on February 3 "in an act of courage." While the popular Pacto Histórico senator was mostly met with cheers and chants of the Chilean protest song, " El pueblo unido jamás será vencido,"

World politics

fromenglish.elpais.com

3 weeks agoFrom the Panama Canal standoff to Honduras: Trump reasserts Washington's grip on Central America

It was not just another bombastic statement in the Republican's provocative style it was the first visible sign of a policy that once again places the region under U.S. oversight. Trump revived old interventionist instincts by interfering in Honduras's presidential election and threatening to cut aid to Central American governments as leverage to force them into agreements aimed at curbing migration.

US politics

fromwww.theguardian.com

1 month agoWhy Spain's prime minister has broken ranks in Europe and dared to confront Trump

This week, Sanchez did not wait for a joint EU statement to issue judgment on the US's illegal military intervention to capture the Venezuelan president, Nicolas Maduro: he swiftly joined Latin American countries in condemning it. A few hours later he went even further, saying the operation in Caracas represented a terrible precedent and a very dangerous one [which] reminds us of past aggressions, and pushes the world toward a future of uncertainty and insecurity, similar to what we already experienced after other invasions driven by the thirst for oil.

Europe politics

fromenglish.elpais.com

1 month agoVenezuelan opposition redefines its strategy with one priority: The return of its leaders in exile

the capture of Nicolas Maduro. However, the outlook darkened as the hours passed, and the main anti-Chavista leaders, headed by Maria Corina Machado, adjusted their priorities in response to Donald Trump's affront. While the initial reaction of the opposition leadership was a willingness to immediately replace Chavismo, the harsh reality imposed by the Republican president's choice of Delcy Rodriguez ultimately redefined their strategy.

World news

fromTruthout

1 month agoAs Trump Expands Imperial Aggression in Venezuela, Corporate Media Falls in Line

I watched the January 3 rd nightly coverage on CBS and NBC of the U.S. assault on Venezuela and the kidnapping of President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, and what I witnessed was not journalism but the choreography of propaganda. CBS, in particular, offered thirty uninterrupted minutes of state-sanctioned fantasy, anchored by a fawning interview with Secretary of War Pete Hegseth, a man implicated in the killing of more than one hundred people at sea without evidence, accountability, or due process.

US politics

fromThe Atlantic

1 month ago'Have Fun in Jail'

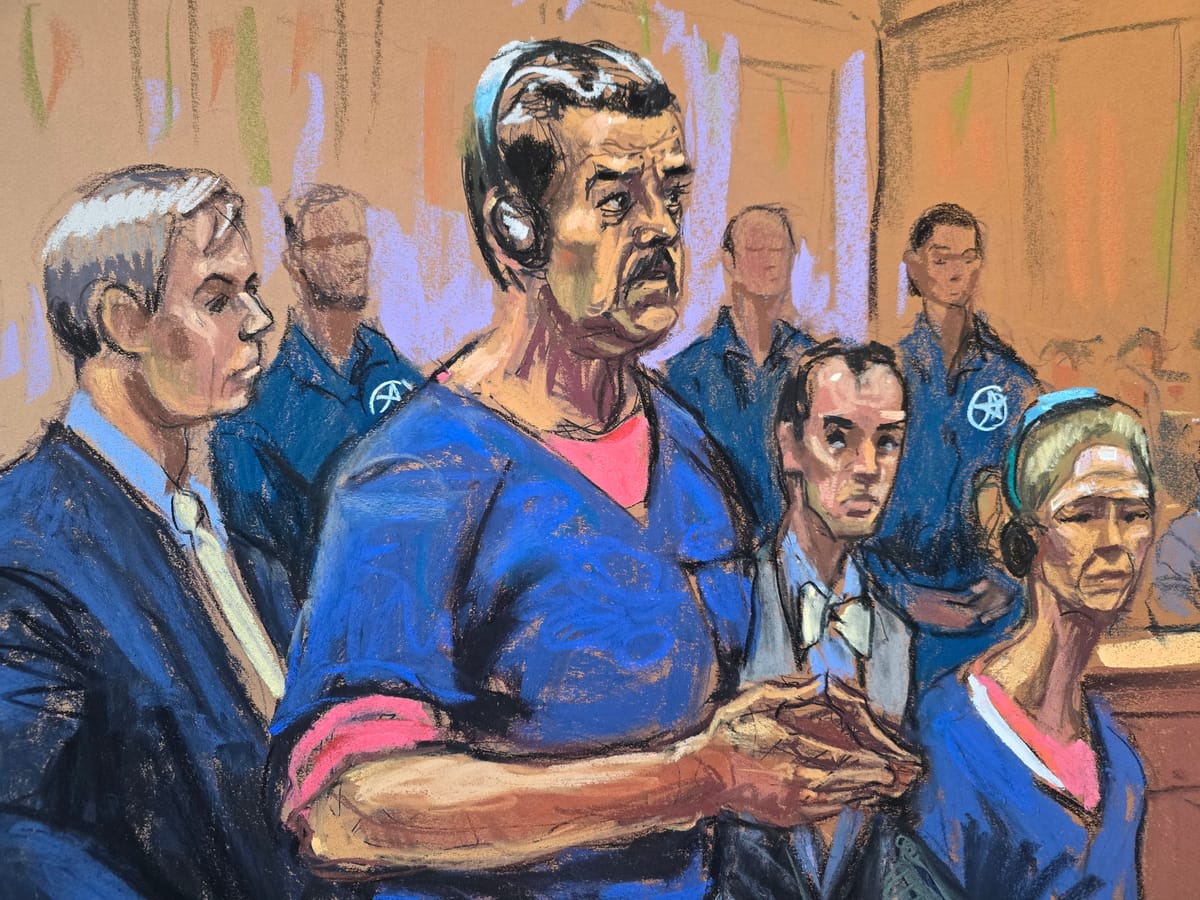

Nicolás Maduro wasn't due to arrive at his arraignment yesterday in downtown Manhattan until noon, but a large crowd had already formed outside the federal courthouse by 9 a.m. Actually, two crowds. One had come to tell Donald Trump to keep his hands off Venezuela. The other, which seemed largely Venezuelan, had come to celebrate. Maduro was, until Saturday, a widely hated ruler. His last election campaign consisted of threatening his people with a "bloodbath" if he lost.

World news

World news

fromwww.theguardian.com

1 month agoOpposition leader Machado says she hasn't spoken to Trump since attack as she vows to return to Venezuela live

More than a dozen media workers were detained in Caracas while covering pro-Maduro events; all 14 were released but one foreign journalist was deported.

World politics

fromwww.mediaite.com

1 month agoThe View' Audience Applauds as Ana Navarro Revels in Capture of Sadistic Son of a B*tch' Maduro

Ana Navarro celebrates the capture of Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro, condemns his 25-year oppression, and criticizes Trump’s comments about opposition leader María Corina Machado.

Brooklyn

fromBrooklyn Paper

1 month agoProtesters rail against Venezuelan despot Nicolas Maduro outside Metropolitan Detention Center * Brooklyn Paper

More than 100 New York protesters condemned the U.S. seizure of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro as illegal, destabilizing, and motivated by oil interests.

World news

fromABC7 San Francisco

1 month agoNicolas Maduro arrives at Manhattan federal court for arraignment

Nicolás Maduro was captured, transported to Manhattan federal court, and arraigned on a four-count indictment including drug-trafficking conspiracy after a U.S.-led operation removed him from power.

fromLos Angeles Times

1 month agoTies between California and Venezuela go back more than a century with Chevron

As a stunned world processes the U.S. government's sudden intervention in Venezuela - debating its legality, guessing who the ultimate winners and losers will be - a company founded in California with deep ties to the Golden State could be among the prime beneficiaries. Venezuela has the largest proven oil reserves on the planet. Chevron, the international petroleum conglomerate with a massive refinery in El Segundo and headquartered, until recently,

World news

US politics

fromwww.amny.com

1 month agoNew York Venezuelans have mixed feelings about Nicolas Maduro's arrest and detention in the Big Apple amNewYork

Venezuelans in New York reacted with relief, outrage, and uncertainty to the U.S. capture of Nicolas Maduro, reflecting divisions over U.S. intervention and future stability.

US politics

fromwww.mediaite.com

1 month agoTulsi Gabbard Said US Cycle Of Regime Change' Was Over Just 2 Months Before Maduro Arrest

DNI Tulsi Gabbard praised ending U.S. regime-change interventions while previously warning against Venezuelan military intervention, shortly before the U.S. captured Nicolás Maduro.

US politics

fromFortune

1 month agoWhat is the Monroe Doctrine? Here's how it has shaped U.S. foreign policy for two centuries, including Trump's ouster of Maduro | Fortune

The Monroe Doctrine, originally opposing European interference in the Americas, has been repeatedly invoked to justify U.S. interventions, including recent efforts regarding Venezuela.

[ Load more ]