#propaganda

#propaganda

[ follow ]

#north-korea #russia #south-korea #iran #social-media #china #military-casualties #melania-trump #documentary #ice

fromwww.theguardian.com

1 week agoA white man's war, a Black man's fight': the eye-opening story of Black soldiers in Vietnam

Carefully, he takes out a flier, yellowed and brittle with age. The text at the top is Vietnamese. Underneath there is English. It reads: Colored Gl's! The South Vietnamese people, who are struggling for their independence and freedom, are friends with the American colored people being victim of barbarous racial discrimination at home. Your battlefield is right in the USA! Your enemy is the war lords in the White House and the Pentagon!

Social justice

fromLGBTQ Nation

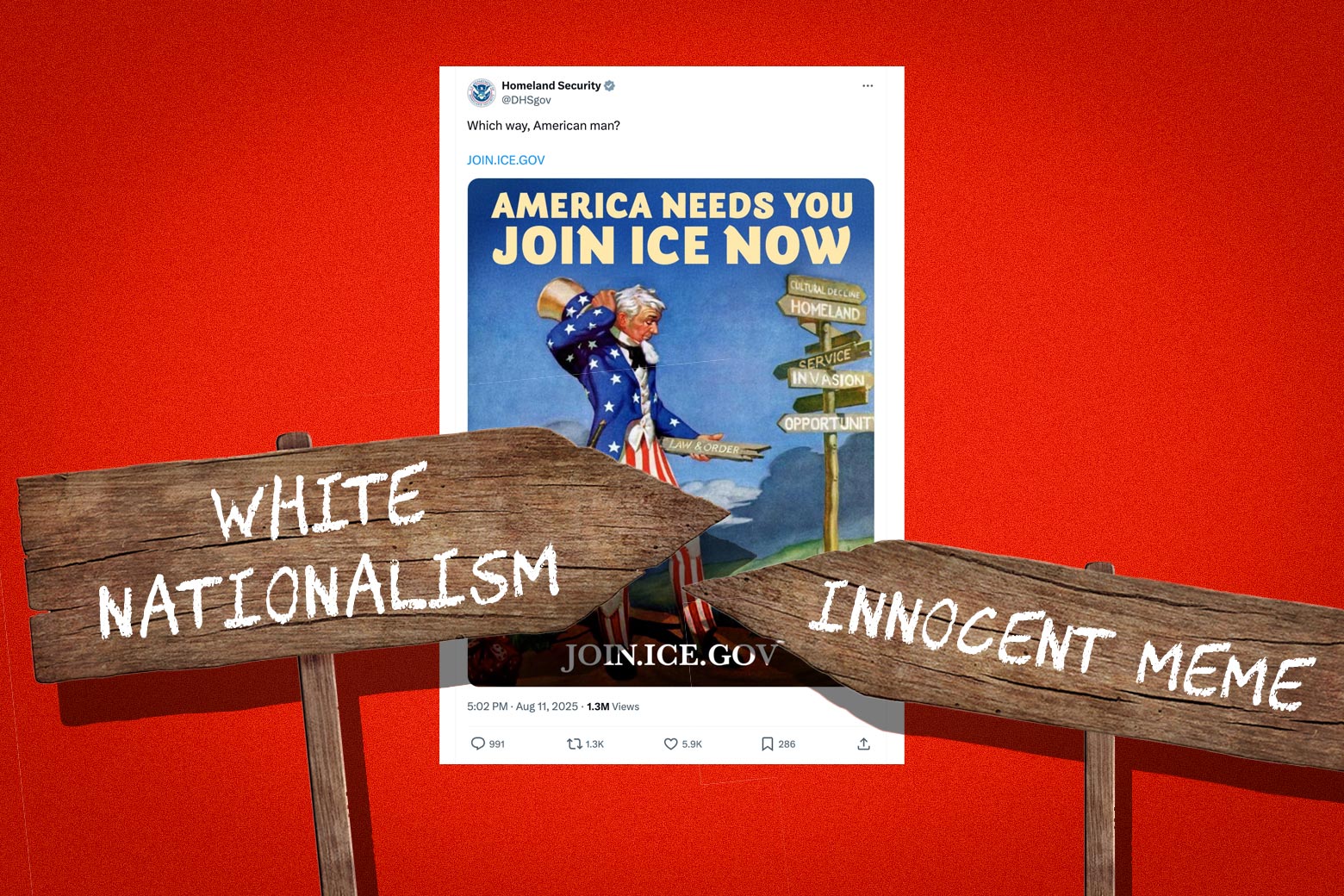

1 week agoTrump's immigration war certainly exposed the "worst of the worst." But it's far from who he thinks. - LGBTQ Nation

You took an oath to protect and serve. To keep your family, your neighborhood safe. But in too many cities, dangerous illegals walk free as police are forced to stand down. Join ICE and help us catch the worst of the worst: drug traffickers, gang members, predators. Join the mission to protect America with bonuses up to $50,000, student loan forgiveness, and generous benefits. Apply now... and fulfill your mission.

US politics

fromOpen Culture

2 weeks agoHannah Arendt Explains How Propaganda Uses Lies to Erode All Truth & Morality: Insights from The Origins of Totalitarianism

At least when I was in grade school, we learned the very basics of how the Third Reich came to power in the early 1930s. Paramilitary gangs terrorizing the opposition, the incompetence and opportunism of German conservatives, the Reichstag Fire. And we learned about the critical importance of propaganda, the deliberate misinforming of the public in order to sway opinions en masse and achieve popular support (or at least the appearance of it).

Online learning

fromLos Angeles Times

4 weeks agoCommentary: This is not normal: Why a fake arrest photo from the White House matters

Even in an age of misinformation and disinformation - which we really need to start clearly calling propaganda - we continue to rely on old ways of knowing. We take it for granted that if we really need to get to the truth, there's a way to do it, even if it means cracking the pages of one of those ancient conveyors of wisdom, a book.

US politics

fromJezebel

1 month agoThe White House Is Amplifying Fake Accounts of 'Sonic Weapons' in Venezuela

There was once a time when the White House Press Secretary retweeting accounts of the novel deployment of high-tech weaponry against human targets would have been global news, but what goes unsaid is that in this previous timeline, the press secretary would have been citing an actual source, with a real story to share, rather than a piece of propaganda that has clearly been manufactured for an obvious purpose.

US politics

Film

fromwww.theguardian.com

1 month agoPutin as a Russian James Bond? Jude Law's Vladimir film seems to have swallowed Kremlin myths | Natasha Kiseleva

State-aligned Russian media and pop culture manufacture a heroic, mythic Putin image that western portrayals sometimes reinforce rather than challenge.

Miscellaneous

fromLondon Business News | Londonlovesbusiness.com

2 months agoThe space between peace and war: Hostile states are weaponising free speech - London Business News | Londonlovesbusiness.com

Western democracies must protect free speech while preventing participation in foreign information warfare that constitutes assistance to hostile states.

fromwww.theguardian.com

2 months agoIt's the media's job to hold power to account. This year, too many got into bed with it instead | Arwa Mahdawi

Almost a decade ago I decided to quit my well-paid job in advertising in order to pursue a precarious career in freelance journalism. The merits of that decision are up for debate but the real stupidity is in how I quit my job: I wrote a rather cringeworthy column for the Guardian about my meaningless job in advertising and publicly proclaimed that I'd decided to quit.

Media industry

Miscellaneous

fromwww.mediaite.com

2 months agoAfter Putin Claims Ukrainian Troops Were Surrounded, Zelensky Shows Up and Posts Selfies

Zelensky visited Kupiansk, posted frontline video and selfies proving Ukrainian presence and control despite Kremlin claims, while the city continues to face Russian shelling.

Arts

fromThe Art Newspaper - International art news and events

2 months ago'An entertainment pavilion on bones': new Russian museum opens in occupied Mariupol

Russian-run museum in occupied Mariupol glorifies the invasion, framing it as liberation from "neo-Nazis" and linking it to the Soviet WWII victory.

fromTruthout

2 months agoHillary Clinton Says Young People Oppose Gaza Genocide Because of "Totally Made Up" Videos

Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has claimed that the ignorance of young people and their consumption of content on social media is responsible for their opposition to Israel and its genocide in Gaza, blaming "made up" propaganda on Tuesday while speaking at a conference held by a far right Israeli publication. In remarks on Tuesday, Clinton said that the sentiments among young people following the October 7, 2023, attack are a "serious problem for democracy"

US politics

fromMail Online

2 months agoUS Army's secret mind-control unit releases chilling recruitment video

The clip opens on a burning 1980s CRT television that flickers to life with the dancing ghost from Fleischer Studios' 1930 cartoon 'Swing You Sinners!' Within seconds, the screen jumps to a dark forest where leaflets fall through the trees, followed by shots of soldiers standing among civilians as the words 'We are everywhere' flash across the frame. The video then appears to rewind to a WWII-era bombing run, showing a plane dropping pamphlets over a crowd below.

US politics

fromLos Angeles Times

3 months agoThis L.A. woman was jailed as a WWII traitor. How a pair of perjuries ensnared 'Tokyo Rose'

Her name was Iva Toguri D'Aquino, and she was born in Watts to Japanese parents in 1916 and had a degree in zoology from UCLA. She wanted to be a doctor. But she traveled to Tokyo in 1941 to care for a sick aunt, with disastrous timing. She made the trip without a passport, which doomed her desperate efforts to board a ship home as the war erupted.

History

fromenglish.elpais.com

3 months agoA Russian army unit's macabre contest to pose with executed Ukrainian prisoners of war

A Russian soldier, with his face blurred, poses in front of the bodies of three Ukrainian soldiers lying face down in a pool of blood, their hands clasped behind their heads. The image, shared by the Russian Rusich unit on its Telegram channel, is accompanied by an announcement for a contest: The first three people to submit a photo of prisoners who have clearly been erased from existence will receive a cryptocurrency reward.

Miscellaneous

fromsilive

3 months agoCollege of Staten Island professor honored for book on media strategies | In Class column

Published in 2024, the book offers a critical examination of how Turkey's ruling Justice and Development Party has sought to reposition the country on the world stage. In the 2010s, the party launched an English-language media system to elevate Turkey's image, counter Western criticism of its increasingly authoritarian practices, and promote its own geopolitical and economic interests. Yesil's analysis traces how party-backed outlets frame Turkey as a champion of the oppressed and a counterweight to Western powers,

World news

fromwww.theguardian.com

3 months agoHow Britain replaced the US as Russia's villain of choice

In recent years, Britain has become the villain of choice in Moscow's eyes. It has been accused of plotting drone strikes on Russian airfields, blowing up the Nord Stream pipeline, directing terrorist raids inside Russia, and even abetting last year's gruesome Islamic State concert attack in Moscow. This week, a new charge was added to the pile: Russian authorities claimed that British intelligence had tried and failed to lure Russian pilots into defecting to the west.

World news

fromThe Atlantic

4 months agoIt's Not Enough to Read Orwell

George Orwell was dying when he wrote 1984 in the late 1940s on the desolate Isle of Jura in Scotland's Inner Hebrides. Tuberculosis ravaged his body, and typing thousands of words a day only weakened him further. His skin flaked off. Blisters burst across his throat. Feverish and emaciated, he endured painful procedures to support his failing lungs, but the treatments were too late. Eventually, in 1950, Orwell succumbed to the disease.

Film

fromThe New Yorker

4 months agoAmong the Talibros

Three hostages kneel in front of a camera, their hands tied behind their backs and their heads covered with black plastic bags that obscure their faces. Looming behind them is a group of bearded, glowering militants, dressed in tunics and turbans, some holding assault rifles. "We have one message for America," the man standing in the middle says, with one hand resting on the shoulder of the kneeling figure in front of him, the other hand jabbing the air to emphasize his speech.

World news

fromwww.theguardian.com

5 months agoFrom Nazi Germany to Trump's America: why strongmen rely on women at home

In 1980, Gertrud Scholtz-Klink, an unrepentant former leader of the Nazi women's bureau in Berlin from 1934 to 1945, described her former job to historian Claudia Koonz as influencing women in their daily lives. To her audience approximately 4 million girls in the Nazi youth movement, 8 million women in Nazi associations under her jurisdiction, and 1.9 million subscribers to her women's magazine, Frauen Warte, according to Koonz Scholtz-Klink promoted what she called the cradle and the ladle, or reproductive and household duties as essential to national strength.

History

World politics

fromThe Cipher Brief

5 months agoRiding the Tiger: Why Xi and Putin's 'Axis of Autocracies' Could End the Way Churchill Predicted

Authoritarian leaders exploited political radicalization and propaganda, dismantled democratic institutions, and led their nations into catastrophic wars driven by ambition and delusion.

US politics

fromwww.aljazeera.com

6 months agoIsrael's starvation denial is an Orwellian farce

Israeli hasbara obfuscates the humanitarian crisis in Gaza, challenging the validity of stark images of suffering.

International media coverage of Gaza's plight fluctuates, influenced by visceral imagery and counter-narratives.

US politics

fromenglish.elpais.com

7 months agoAzmi Bishara, former Palestinian member of the Israeli Parliament: Starting a genocide in Gaza was a political decision'

Azmi Bishara critiques the narrative of victimhood in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, arguing that historical injustices shape current perceptions.

[ Load more ]