#income-inequality

#income-inequality

[ follow ]

#consumer-spending #k-shaped-economy #housing-affordability #inflation #labor-market #cost-of-living

fromwww.housingwire.com

18 hours agoStudent loan delinquencies jumped, and housing distress is building

Delinquency rates across mortgages, credit cards, auto loans and student debt have climbed to their highest levels in nearly a decade, reaching 4.8% of outstanding household debt in the fourth quarter. While headline numbers remain within long-term historical ranges, a closer look reveals where stress is building: lower-income ZIP codes, younger borrowers, and markets experiencing slowing or declining home values.

US news

History

fromFortune

1 week agoWhy your boss loves AI and you hate it: corporate profits are capturing your extra productivity, and your salary isn't | Fortune

Technological revolutions boost productivity but often leave worker pay stagnant for decades, risking a repeat of Engels' pause amid today's AI-driven transformation.

fromwww.mercurynews.com

2 weeks agoClendaniel: Declining morality of Silicon Valley's tech leaders dragging down the nation

For 40 years I have been a proud valley resident. But I am increasingly appalled by how our tech leaders are shaping our future. And, more recently, embarrassed for the valley. The links to Jeffrey Epstein. The trips to Mar-a-Lago. The donation of millions for monuments to President Trump's ego. The failure to use power and technology to call out the cruelty and lies that are the backbone of the current administration.

Tech industry

Business

fromFortune

2 weeks agoThe economy isn't K-shaped. For 87 million, people, it's desperate and for another 46 million it's elite | Fortune

A split in consumer confidence across income groups threatens stability as millions facing affordability-driven strain begin abandoning long-term planning and exiting upward mobility.

US politics

fromBusiness Insider

3 weeks agoTrump's former chief economic advisor says workers are 'suffering' in America's K-shaped economy

The US economy shows robust overall growth while many Americans face acute affordability struggles, widening wealth gaps and shifting political focus ahead of midterm elections.

fromAxios

4 weeks agoThe 3 groups lagging most in America's post-COVID rebound

The latest Census data also suggest the next phase of U.S. politics will be shaped less by a single national economy than by who benefited from growth and where they live. By the numbers: The U.S. median household income rose to $80,734, the 2020-2024 American Community Survey released Thursday and examined by Axios showed. That's a 4.4% jump from 2015-2019 after inflation.

US politics

US politics

fromFortune

1 month agoJamie Dimon says he'd have no issue paying higher taxes if it actually went to the people who need it-right now it just goes to the Washington 'swamp' | Fortune

Double the earned income tax credit as a negative income tax, funded by higher taxes on the wealthy, to increase spending for lower-income households.

New York City

fromwww.amny.com

1 month agoZohran Mamdani's inauguration: New mayor vows not to soften democratic socialist agenda for governing NYC amNewYork

Zohran Mamdani pledges to govern New York City as a democratic socialist and implement bold policies tackling inequality, housing, childcare, and public transit.

fromJezebel

2 months agoGambling Is Ubiquitous Because People Know America Is a Scam

The dirty secret many now understand is that a lot of wage labor is not enough to get by in America anymore. The past promise of working hard for 40 hours per week and getting a home and a retirement in return is gone for a significant chunk of this country, stripped away by capitalists whose only desire in their miserable lives is to have more than they currently do.

US politics

Artificial intelligence

fromwww.theguardian.com

2 months agoMost people aren't fretting about an AI bubble. What they fear is mass layoffs | Steven Greenhouse

AI-driven automation risks causing massive job losses, particularly among entry-level white-collar workers, potentially worsening unemployment and income inequality.

Digital life

fromIndependent

2 months ago'There was one lean month this year where I could only pay myself 100' - how much money are influencers really making?

Top influencers can earn millions while most content creators earn less than minimum wage and face privacy invasion, emotional harm, and unstable income.

fromenglish.elpais.com

3 months agoThe rich marry the rich: How love perpetuates inequality

Social class permeates all aspects of life, and love is no exception. In Spain, for instance, couples don't form randomly; rather, they're typically determined by socioeconomic factors. This means that people tend to partner with those most similar to themselves in terms of income and wealth. And, at the top of the social ladder, this tendency intensifies. Those who earn and have the most assets find each other with a frequency three times greater than would occur in a society where relationships were completely random.

Relationships

fromFortune

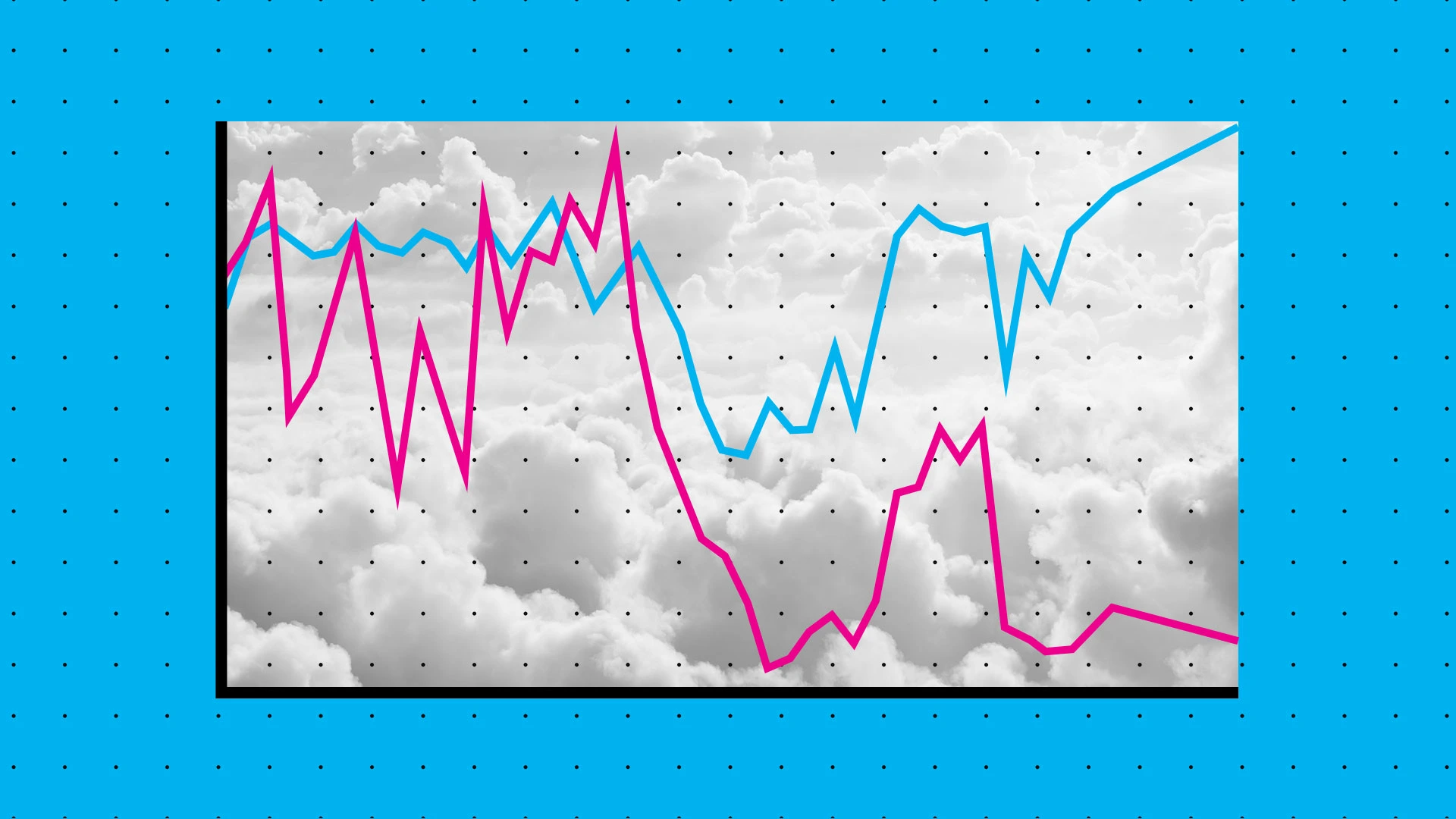

3 months agoTop analyst sees 'genuine cracks for mid- to lower-end consumers' as the K-shaped economy continues to bite | Fortune

The narrative surrounding the "resilient U.S. consumer," which has been a major upside surprise in 2025, is now facing significant headwinds, according to the Global Investment Committee (GIC) at Morgan Stanley Wealth Management. While consumer spending has maintained a steady nominal growth rate of 5% to 6%, underpinning a bullish outlook for US equities in 2026, the GIC is expressing caution. Lisa Shalett, chief investment officer and head of the GIC, warned that although the broader macroeconomic picture remains cautiously optimistic, the "K-shaped" economy demands greater scrutiny.

US news

fromFortune

3 months agoThe K-shaped economy has come for your wages, as lower-income Americans sees their gains plummet to the weakest rate in a decade | Fortune

A decade ago, low-income workers saw wages grow at the highest rate of any Americans. Now, the opposite is true, and the gap is widening between how quickly wages increase for wealthy and poorer U.S. households. In a Monday blog post titled "K-shaped economy," Apollo chief economist Torsten Slok warned the growing disparity is yet another sign of today's economy continuing to serve the rich, while poor Americans continue to struggle.

US news

Business

fromFortune

3 months agoUlta Beauty CEO Kecia Steelman went from earning $8 an hour to running the U.S.'s largest beauty retailer | Fortune

Government shutdown-related SNAP payment disruptions cost stores revenue, harm low-income households, and underscore how U.S. consumer spending and transfers sustain the economy amid rising inequality.

US politics

fromwww.mediaite.com

3 months agoJon Stewart Rips Trump's Great Gatsby-Themed Ode to Decadence and Hedonism': Even Jeffrey Epstein Would Have Thought' It Was Too Much

Trump hosted a Great Gatsby-themed Mar-a-Lago party as SNAP benefits ended, drawing criticism for celebrating decadence amid rising hardship and income inequality.

fromwww.theguardian.com

3 months agoThe Guardian view on Britain's new class divide: the professional middle is being hollowed out | Editorial

An Oxford don in charge of mathematical finance told its reporters that almost all his students ended up working at quant trading firms, on salaries from 250,000 to 800,000. If you get offered a salary less than 250K, you're kind of the sad guy, he said, adding that nobody I know interviews for JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs not once do I hear anybody entertain any of these traditional investment banking jobs.

UK politics

US politics

fromwww.npr.org

4 months agoIn 'Fight Oligarchy,' Sen. Bernie Sanders calls for a political revolution

Oligarchic control and billionaire influence have corrupted U.S. politics, producing extreme inequality and necessitating a working-class–centered political revolution and community mobilization.

fromBoston Condos For Sale Ford Realty

4 months agoBoston Condos For Sale And The Two-tier Economy Boston Condos For Sale Ford Realty

For high-income consumers ("the haves"): Strong spending power: Wealthy consumers are buoyed by high asset prices in stocks and real estate. The market melt-up, fueled by investments in areas like artificial intelligence, has increased their net worth. Insulation from interest rates: These individuals are less affected by higher interest rates, allowing them to continue spending on both luxury items and daily goods. Confidence in the economy: Their financial confidence remains strong, leading to continued investment and consumption.

Business

US politics

fromFast Company

4 months agoThe biggest U.S. companies on the S&P 500 spent more than $1 trillion on stock buybacks and dividends in 2024

Major U.S. corporations prioritized over $1.6 trillion in 2024 for buybacks and dividends, outpacing taxes and diverting funds from wages and sustainable investments.

Mental health

fromwww.theguardian.com

4 months agoStudy links greater inequality to structural changes in children's brains

State-level income inequality associates with reduced cortical surface area and altered brain connectivity in children across socioeconomic backgrounds, and links to poorer mental health.

Business

fromFortune

5 months agoEntrepreneurs can make up to 70% more than paid employees per year, but there's high inequality among the self-employed | Fortune

Entrepreneurs start with lower incomes but surpass employees by age 30 and earn substantially more by career stage, with high inequality concentrated among top earners.

fromenglish.elpais.com

5 months agoThe social elevator is breaking down in Spain, one of the richest countries with the greatest inequality of opportunity

Economists have long warned that the upward climb has slowed to a near standstill. Now the OECD has provided figures that reinforce this perception: in Spain, more than a third of income inequality is determined by factors that do not depend on the individual, but rather on imposed or inherited circumstances such as gender, the parents' place of birth, or, above all, their socioeconomic background.

Miscellaneous

fromwww.mercurynews.com

5 months agoWalters: California's sky-high costs afford it highest poverty label again

Last year's presidential election underscored, particularly to Democrats, that the costs of living were a major factor in the outcome. Inflation had increased sharply during Joe Biden's presidency, and voters' angst about rising prices worked against Vice President Kamala Harris' campaign to succeed him in the White House. Not surprisingly, therefore, when the California Legislature opened its 2025 session, its dominant Democrats declared that they would focus on taming the state's notoriously high costs for housing, fuel, utilities and other necessities of modern life.

California

Left-wing politics

fromwww.mediaite.com

5 months agoTwitch Star Hasan Piker: 'Capitalist Way of Life' Contributed to Charlie Kirk Shooting

The murder of a high-profile conservative content creator reflects social breakdown driven by capitalism, worsening material conditions, isolation, resentment, and a 24/7 news cycle.

[ Load more ]