#human-computer-interaction

#human-computer-interaction

[ follow ]

#artificial-intelligence #user-experience #ai #technology #large-language-models #augmented-reality #meta

fromTechCrunch

3 weeks agoElevenLabs CEO: Voice is the next interface for AI | TechCrunch

ElevenLabs co-founder and CEO Mati Staniszewski says voice is becoming the next major interface for AI - the way people will increasingly interact with machines as models move beyond text and screens. Speaking at Web Summit in Doha, Staniszewski told TechCrunch voice models like those developed by ElevenLabs have recently moved beyond simply mimicking human speech - including emotion and intonation - to working in tandem with the reasoning capabilities of large language models.

Artificial intelligence

fromSmithsonian Magazine

1 month agoWhy the Computer Scientist Behind the World's First Chatbot Dedicated His Life to Publicizing the Threat Posed by A.I.

It could have been a heart-to-heart between friends. "Men are all alike," one participant said. "In what way?" the other prompted. The reply: "They're always bugging us about something or other." The exchange continued in this vein for some time, seemingly capturing an empathetic listener coaxing the speaker for details. But this mid-1960s conversation came with a catch: The listener wasn't human. Its name was Eliza, and it was a computer program that is now recognized as the first chatbot,

History

fromFigma

1 month agoSoftware Is Culture

Software used to feel separate from us. It sat behind the glass, efficient and obedient. Then it fell into our hands. It became a thing we pinched, swiped, and tapped, each gesture rewiring how we think, feel, and connect. For an entire generation, the connection to software has turned the user experience into human experience. Now, another shift is coming. Software is becoming intelligent. Instead of fixed interactions, we'll build systems that learn, adapt, and respond.

UX design

fromScatterarrow

3 months agoAll Your Coworkers Are Probabilistic Too

If you've worked in software long enough, you've probably lived through the situation where you write a ticket, or explain a feature in a meeting, and then a week later you look at the result and think: this is technically related to what I said, but it is not what I meant at all. Nobody considers that surprising when humans are involved. We shrug, we sigh, we clarify, we fix it.

fromMedium

3 months agoThe shortest path from thought to action

When psychologist Paul Fitts published his 1954 paper on human motor control, he likely had no idea that his insights would one day guide the design of everything from smartphones to virtual worlds. Fitts conducted his experiments using simple physical apparatuses, such as levers, styluses, and lighted targets, to measure how quickly participants could move and point to targets of varying sizes and distances. These experiments were precursors to the pointing and selection tasks that would later define human-computer interaction.

Mobile UX

fromMedium

3 months agoFrom design to direction: Bridging product design and AI thinking

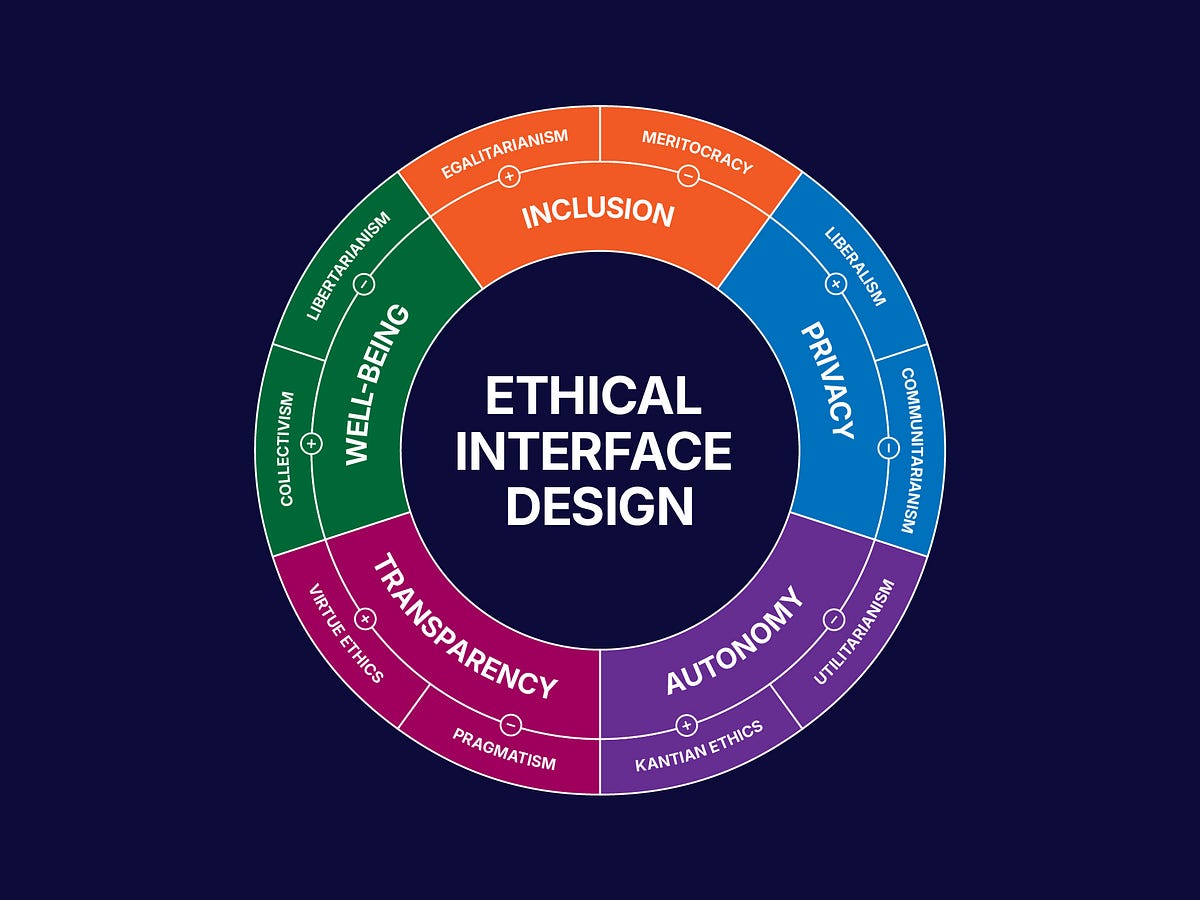

A lot has been written about the evolution of user experience since before I ever sat in a Barnes & Noble for hours, trying to understand what the letters "H, C, and I" even meant. In the twelve years since that moment, the tools we use have matured, the rules for interaction have solidified, and the role of design has expanded. We have become a bridge connecting users, businesses, and the technologies that serve them.

Artificial intelligence

UX design

fromLogRocket Blog

3 months agoI think the next UX era will shock us: Here are my 3 big predictions - LogRocket Blog

UI/UX design evolved from complex, function-first interfaces to minimalist, user-centric ones and will continue evolving with HCI innovations toward more intuitive, accessible futuristic UIs.

fromYanko Design - Modern Industrial Design News

4 months agopicoRing Mouse Research Explores Ultra-Low-Power Wearable Input - Yanko Design

The future of computing increasingly demands input devices that work seamlessly in mobile, public, and wearable contexts where traditional mice become impractical or socially awkward. As we move toward augmented reality, smart glasses, and always-connected devices, the need for subtle, continuous interaction grows more pressing. Current solutions often require bulky hardware, frequent charging, or obvious gestures that draw unwanted attention.

Gadgets

fromAcm

4 months agoCyberpsychology's Influence on Modern Computing

Cyberpsychology investigates the psychological processes related to technologically interconnected human behavior, informing disciplines such as human-computer interaction (HCI), computer science, engineering, psychology, and media and communications studies.5 The field explores how digital technologies influence and transform human cognition, emotion, and social interaction, as well as the reciprocal impact these human elements have on technologies. At its core, cyberpsychology seeks to understand the dynamic interplay between humans and technology.

Artificial intelligence

UX design

fromUX Magazine

4 months agoDesigning the Invisible between humans and technology: My Journey Blending Design and Behavioral Psychology

Design must prioritize trust, reliability, and psychological understanding to create AI systems that remember, support, and form meaningful human-technology relationships rather than polished interfaces.

Artificial intelligence

fromenglish.elpais.com

5 months agoPilar Manchon, director at Google AI: In every industrial revolution, jobs are transformed, not destroyed. This time it's happening much faster'

Pilar Manchon views AI as a security-first, responsibly developed instrument capable of building a better society and guiding humanity toward a new Renaissance.

Video games

fromwww.theguardian.com

5 months agoWhy do some gamers invert their controls? Scientists now have answers, but they're not what you think

Inverted controller preferences persist because early exposure, professional training, and diverse sensorimotor experiences shape users' control mappings and configurations.

fromSocial Media Today

5 months agoMeta Showcases New AI Glasses, VR Upgrades, at Connect 2025

The star of Meta Connect 2025 is Meta's new Ray-Ban-branded Display AI glasses, which include a heads-up display element to overlay info on the wearer's view. Meta's "neural wristband", which Zuckerberg described as "the next chapter in the exciting story of the history of computing," uses The end result is a whole new way of interacting with the digital environment, which Meta's hoping will become the foundation for its future AR and VR projects.

Gadgets

[ Load more ]