Science

Science

[ follow ]

Science

fromwww.scientificamerican.com

1 hour agoInterstellar Comet 3I/ATLAS captured speeding through the solar system by Jupiter-bound spacecraft

Comet 3I/ATLAS, an interstellar visitor from outside our solar system, traveled through our cosmic neighborhood at speeds exceeding 150,000 miles per hour, displaying behavior consistent with normal comets despite its mysterious origin.

Science

fromwww.theguardian.com

7 hours agoWho'd guess they're the same species?' What Italy's wall lizards reveal about genetic diversity and why it matters

Biodiversity encompasses variation within species, not just species inventory, as demonstrated by common wall lizards showing dramatic differences in color, size, and behavior despite being the same species.

fromBig Think

1 day agoAsk Ethan: Can quantum entanglement survive a black hole?

According to Einstein's General Relativity, for every black hole that exists within the Universe, there are only three properties that go into it that matter in any way: the black hole's total mass, the black hole's net electric charge, and the black hole's intrinsic angular momentum, and that's it. It doesn't matter what type of matter went into the black hole in order to form it; all that matters is its mass, charge, and angular momentum.

Science

fromNature

1 day agoPokemon turns 30 - how the fictional pocket monsters shaped science

It influenced my idea of what animals and natural history were, almost before I knew what real animals in the real world were like. For some researchers, themes in the Pokémon games mirror their everyday work. Spencer Monckton, a research scientist at the University of Guelph in Canada, who grew up playing the games and watching the TV series, says that collecting Pokémon is very much the same thing as what an entomologist does.

Science

fromMail Online

1 day agoAliens could be CATAPULTED onto Earth via an asteroid, study claims

We found that life is more likely to survive an asteroid impact, so it's definitely still a real possibility that life on Earth could have come from Mars. Maybe we're Martians! The idea that life could have spread through the solar system or even the universe on rocks is known as the lithopanspermia hypothesis.

Science

fromPsychology Today

20 hours agoIs the Gut-Autism Link Overblown?

The article from the journal argues that the gut-autism axis is a house of cards built on lousy studies with inconsistent data. They assert that the studies are contradictory and that too much emphasis is placed on dubious mouse models. It is notoriously challenging to nail down microbial causes of disease—it is hard enough to simply identify a normal microbiome.

Science

Science

fromwww.scientificamerican.com

17 hours agoIs there lightning on Mars? New evidence suggests it's there, just hard to see

Scientists have detected possible evidence of lightning on Mars, with the phenomenon likely appearing as electrostatically charged dust sparks rather than dramatic bolts due to Mars's thin atmosphere and weak magnetic field.

fromwww.scientificamerican.com

1 day agoHow a teen's AI model could help stop poaching in rainforests

Both species are under threat. But while African savanna elephants are endangered, forest elephants are critically endangered. They're also highly elusive. Living in dense tropical rainforests in central Africa and parts of West Africa they're very hard to find and study.

Science

fromTheregister

20 hours agoHarvard boffins crack the mystery of squeaky sneakers

The results showed that the squeaking sound is produced by wave-like patterns across the rubber surface, contacting and then releasing from the glass, allowing the sliding between the surfaces. The waves move across the interface between the two materials at a speed of nearly 300 kilometers per hour.

Science

fromenglish.elpais.com

23 hours agoAnts trapped in amber reveal what diminutive life was like millions of years ago

Although there are many amber stones containing a single creature, there are fewer that include two or more, as is the case with a pair of mosquitoes trapped in amber 130 million years ago which tell us that, back then, males also sucked blood. Even more extraordinary is when several organisms can be seen interacting, either eating the other, acting as a parasite, or cooperating.

Science

fromNature

1 day agoIs a 'selfish gene' making a Utah family have twice as many boys as girls?

Such sex 'distorters' have been discovered - and studied in great depth - in laboratory animals such as mice and flies, in which their effects can be detected through selective breeding. 'If you look, more often than not, you find them,' says Nitin Phadnis, an evolutionary geneticist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, who co-led the study.

Science

Science

fromwww.scientificamerican.com

2 days agoRubin Observatory has started paging astronomers 800,000 times a night

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory's automated alert system successfully began processing hundreds of thousands of astronomical observations, enabling astronomers to identify significant celestial changes and events from nightly data.

Science

fromwww.npr.org

1 day agoNASA lost a lunar spacecraft one day after launch. A new report details what went wrong

NASA's Lunar Trailblazer mission failed due to software that pointed solar panels 180 degrees away from the sun, combined with multiple cascading fault management errors that prevented correction.

fromBig Think

2 days agoRecord-breaking natural laser discovered 11 billion light-years away

an electron within a molecule gets excited to a higher-energy state, the electron de-transitions back to the lower energy state, where it emits light of a very specific wavelength in the process. Then, pumped or injected energy re-excites an electron within that very same molecule back into that higher-energy state, over and over.

Science

fromTheregister

2 days agoNASA safety watchdog says it's time to rethink Moon landing

Artemis III aims to land astronauts near the lunar South Pole, relying on SpaceX's Starship-derived Human Landing System (HLS) - a vehicle that has yet to achieve orbit, let alone venture anywhere near the Moon. It's an extraordinarily ambitious undertaking, and one the ASAP report has formally classified as high risk.

Science

Science

fromFortune

1 day agoHarvard professor finally cracks the scientific secret of why sneakers squeak during basketball games | Fortune

Basketball shoe squeaks result from tiny sole sections rapidly losing and regaining contact with the floor thousands of times per second, creating ripples that produce the high-pitched sound.

fromTheregister

2 days agoMoon's mighty magnetic field was a 5,000-year titanium blip

Our new study suggests that the Apollo samples are biased to extremely rare events that lasted a few thousand years - but up to now, these have been interpreted as representing 0.5 billion years of lunar history. It now seems that a sampling bias prevented us from realizing how short and rare these strong magnetism events were.

Science

fromwww.scientificamerican.com

1 day agoKatharine Burr Blodgett made a breakthrough when she discovered invisible glass'

In 1938 Blodgett's meticulous experiments with thin film coatings on solid surfaces lead to her most important breakthrough: nonreflecting glass. GE's public relations machine kicks into high gear. Blodgett becomes an overnight sensation in both the scientific community and the press, which dubs her discovery invisible glass. The assistant to the Nobel Prize winner, long invisible herself, takes center stage.

Science

Science

fromwww.theguardian.com

1 day agoNew image reveals secrets of Milky Way galaxy in stunning detail

The Alma telescope captured an unprecedented detailed image of the Milky Way's center, revealing previously unknown filaments of matter flowing to form stars and planets, advancing understanding of galactic formation.

fromFuturism

1 day agoDamage to Chinese Spacecraft Was Worse Than Reported

My first thought was whether a small leaf had somehow stuck to the outside of the window. But then I quickly realized that couldn't happen because we were in space. How could there possibly be a fallen leaf there? We could see very clearly the small cracks [with the microscope]. Several were relatively long, and one was shorter. We could also see that some of the cracks had penetrated through.

Science

fromInside Higher Ed | Higher Education News, Events and Jobs

2 days agoNSF Plans to Boost Staffing, Halve Grant Solicitations

The fewer solicitations you have, the less time grant applicants have to figure out which of our pigeonholes they fit into. In the past, a solicitation might have been for an individual program, which means it's attached to an individual program officer and a specific dollar amount. Now, instead of going to one program officer's area, the NSF will use technology to better route applications to wherever within the agency they can best be reviewed.

Science

Science

fromArs Technica

1 day agoA non-public document reveals that science may not be prioritized on next Mars mission

NASA released a pre-solicitation for a $700 million Mars orbiter spacecraft contract to relay communications and provide navigation support through 2035, with competition expected to be more open than originally intended.

fromItsnicethat

2 days agoThis rocks: Zach Knott's Stone Isles is a geological ode to crystals, science and family

Every black-and-white photograph of the layers of our planet's tectonic history is an act of time travel - it gets us closer to understanding the past and the future of Earth. The photos are proof that the world is ever changing, showing how vast plains of sedimentary materials shift and morph over thousands of centuries.

Science

fromArs Technica

1 day agoThe physics of squeaking sneakers

Tuning frictional behavior on the fly has been a long-standing engineering dream. This new insight into how surface geometry governs slip pulses paves the way for tunable frictional metamaterials that can transition from low-friction to high-grip states on demand.

Science

Science

fromKqed

2 days agoHow to See Tuesday Morning's 'Blood Moon' in the Bay Area | KQED

Lunar eclipses are visible from anywhere on Earth's night side without special equipment, and the upcoming total lunar eclipse will display a red 'blood moon' due to Rayleigh scattering of sunlight through Earth's atmosphere.

fromMail Online

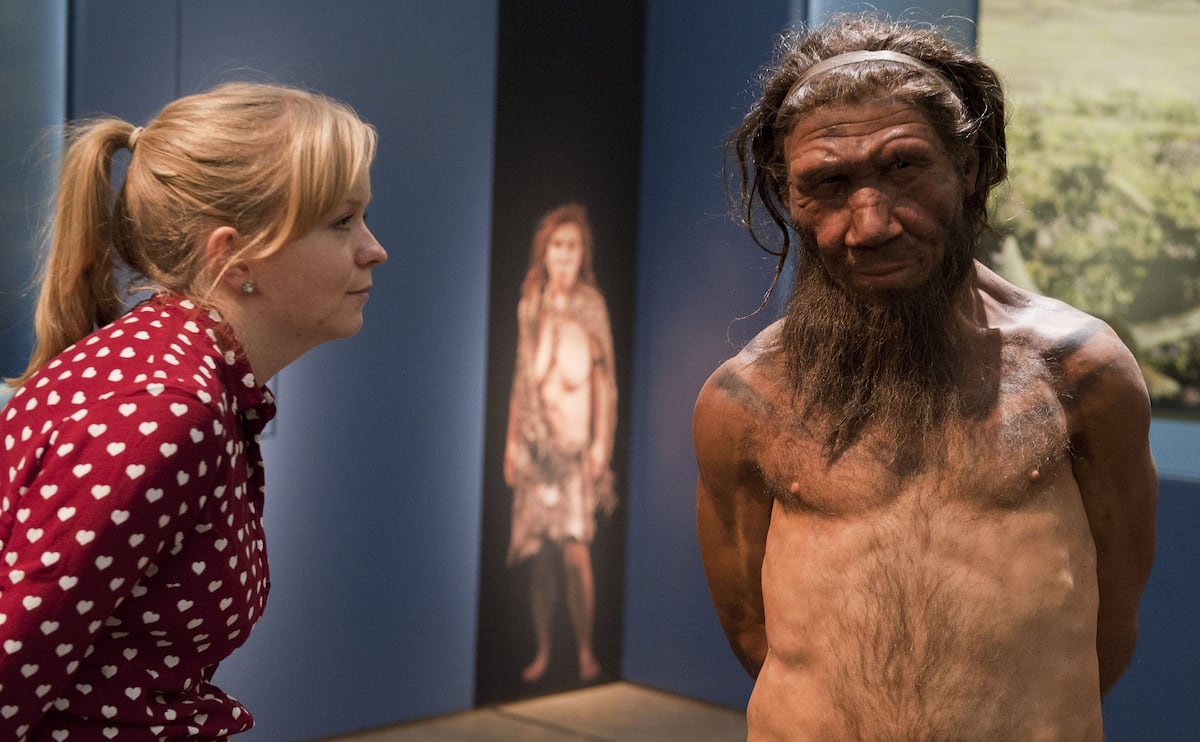

2 days agoWhy women's breasts are so large compared to other animals, revealed

Human breasts sit at an elevated temperature, protecting a newborn from hypothermia. What's more, the size and shape of the breast allows for broad contact surface - enhancing the heat transfer from mother to child. This could improve a newborn's chances of survival and provide an evolutionarily grounded explanation for the development of external breasts in humans.

Science

Science

fromMail Online

1 day agoBiblical earthquake during Jesus' crucifixion confirmed

A 2012 geological study found seismic evidence near the Dead Sea suggesting earthquakes occurred around 31 BC and between 26-36 AD, potentially supporting the Gospel account of an earthquake during Jesus' crucifixion.

fromNature

2 days agoHealth effects linger 20 generations after rats are exposed to fungicide

Exposure to a fungicide induced changes to gene expression in rats that persisted for at least 20 generations. It also increased the chance of offspring developing kidney disease, obesity or experiencing complications when giving birth, according to the longest-running study of 'epigenetic' changes in mammals.

Science

Science

fromNature

4 days agoDaily briefing: COVID's origins - what we do and don't know

Horses produce two-toned vocalizations simultaneously using their vocal folds and larynx cartilage to convey complex messages, while AI threatens research programming jobs and Japan approves stem cell therapies with limited trial data.

Science

fromNews Center

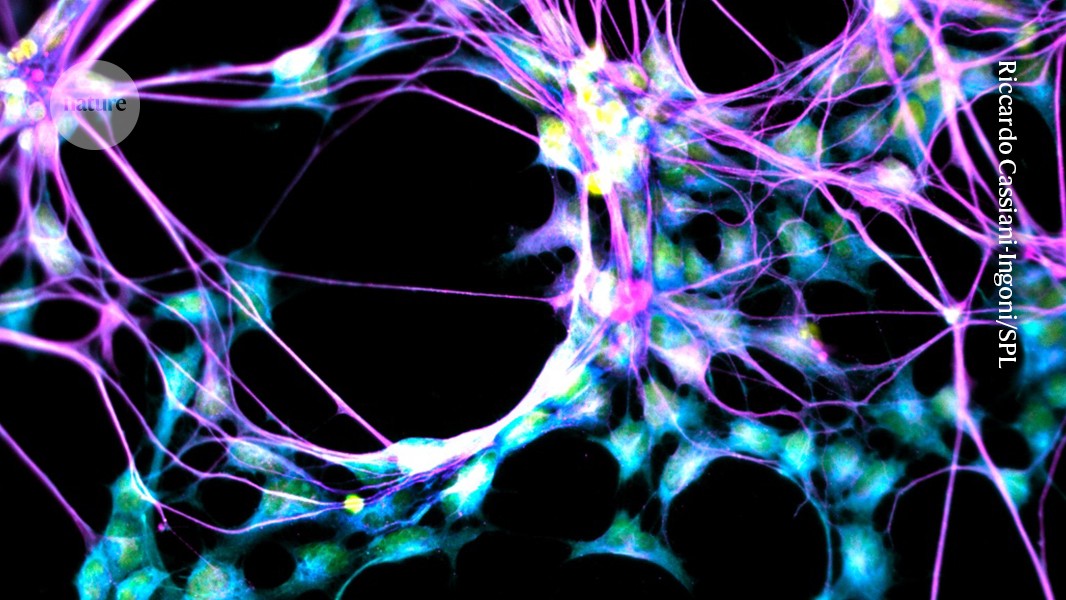

2 days agoLiving 'Mini Brains' Meet Next-Generation Bioelectronics - News Center

Scientists developed a soft 3D electronic mesh that wraps around human neural organoids, enabling comprehensive mapping and manipulation of neural activity across entire miniature brain structures for the first time.

fromWIRED

3 days agoThis Is the Worst Thing That Could Happen to the International Space Station

In the vacuum of space, the amount of debris-spent rocket stages, splintered satellites, micrometeoroids- numbers in the millions, all zooming about, often at 17,000 mph speeds. They're also constantly hitting each other in a tsuris of exponential littering. Most of these pieces are tiny, and many are not anywhere near the altitude of the ISS. But the area isn't completely clean.

Science

fromNature

3 days agoPop-up journals for policy research: can temporary titles deliver answers?

I'm less interested in topics than in questions, and I'm less interested in publishing than I am in curation. When I've testified before Congress or dealt with an appropriations bill or a budget negotiation, this question, of what is the return on investments when you're doing R&D, comes up quite often. It's been asked by economists in very formal ways since at least the 1950s, but the data and the methods that were available were really not very strong.

Science

fromNature

3 days agoFive ways to spot when a paper is a fraud

A growing number of AI tools can detect fraudulent elements in papers, but they can be expensive to use. Such tools are probably better deployed by journal publishers rather than individual reviewers, says Elisabeth Bik, a science-integrity consultant in San Francisco, California, especially because feeding unpublished content into AI tools can compromise confidentiality and is generally frowned on during peer review.

Science

Science

fromwww.scientificamerican.com

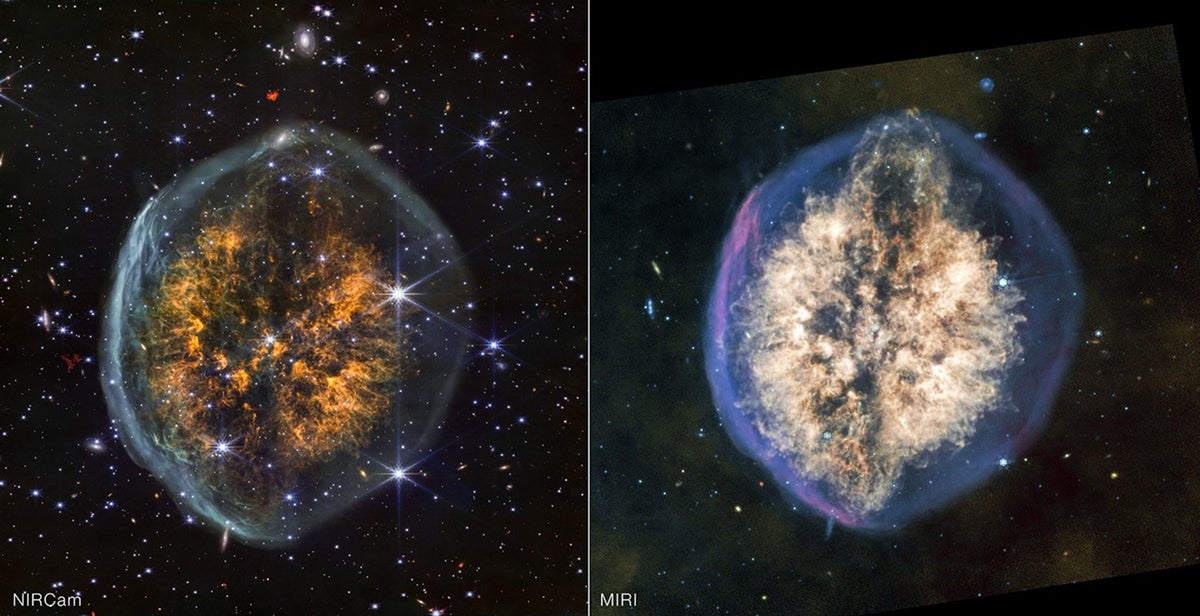

2 days agoAstronomers spot a young sun blowing bubbles inside the Milky Way

NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory captured the first image of a young sunlike star's astrosphere, a protective bubble of hot gas 120 light-years away, revealing how stellar winds shape these cosmic structures.

fromMail Online

3 days agoSee the Milky Way like NEVER before in largest image of its kind

One of the most exciting aspects is the rich chemistry we detect. We see dozens of different molecules, including some complex organic molecules that contain carbon, the same element that forms the basis of life on Earth. From ACES, we are learning more about how the ingredients for planets, and potentially life itself, can arise in the universe.

Science

fromMail Online

3 days agoAliens DO exist - they just haven't visited Earth, NASA veteran claims

'There exists nothing today that says any alien or any alien machine has ever landed on the planet Earth. If you believe otherwise, you are being misled.' Dr. Lee emphasizes that despite widespread UFO claims, no credible evidence supports alien visitation to Earth, and alternative explanations exist for reported phenomena.

Science

Science

fromABC7 Los Angeles

2 days agoNASA's Mike Fincke identifies himself as the ailing astronaut who prompted space station evacuation

Astronaut Mike Fincke experienced a medical event aboard the International Space Station that required early mission termination and evacuation, though his condition stabilized quickly with crew and ground support.

fromNature

3 days agoThe surprising science of squeaky sneakers

Squeaking occurs across various contexts including shoes, bike brakes, rubber tires, and biomedical implants when soft and hard surfaces contact each other. Researchers used high-speed photography to study a rubber block sliding across hard acrylic to identify the source of these sounds. The investigation revealed that pulses similar to earthquake dynamics drive the squeaking phenomenon.

Science

fromwww.nature.com

3 days agoLimitations of probing field-induced response with STM

We demonstrate how the apparent magnetic field induced lattice and CDW intensity change can be explained as a consequence of two independent experimental artifacts: a reconfiguration of atoms at the STM tip apex that alters the amplitudes of CDW modulations, and piezo creep, hysteresis and thermal drift, which artificially distort STM topographs.

Science

Science

fromNature

3 days agoThe first ice-core record of historical atmospheric hydrogen levels

Atmospheric hydrogen levels fluctuate with climate changes and have increased significantly since pre-industrial times due to human activities, requiring consideration in projections of future emissions impacts.

fromMail Online

2 days agoEarthquake strikes America's Heartland above ancient volcanoes

Although Kansas has no active volcanoes, the region marks the southern reach of the Midcontinent Rift System, a massive tectonic event that nearly split North America apart in Earth's distant past. When magma forced its way through the crust during that period, it left behind hardened igneous rock and deep fractures that remain buried thousands of feet underground.

Science

Science

fromNature

3 days agoA membrane-bound nuclease directly cleaves phage DNA during genome injection - Nature

SNIPE is a membrane-bound nuclease defense system in bacteria that directly targets foreign nucleic acids to prevent phage infection through a novel mechanism distinct from established defense pathways.

fromwww.scientificamerican.com

2 days agoThe surprising new physics of squeaky basketball shoes

We were not expecting to find so much richness and depth from a physics point of view underneath the sole of a shoe, says Adel Djellouli, a scientist at Harvard University and co-lead of the study. In a new study, scientists explore the physics that give rise to the familiar squeak of basketball shoes sliding on a hard surface.

Science

Science

fromwww.theguardian.com

3 days agoHumans not Mimmo the dolphin need managing in Venice lagoon, say scientists

Italian scientists monitoring a solitary dolphin in Venice conclude that human behavior management, not wildlife control, is necessary to protect the animal from boat propeller dangers.

fromNature

3 days agoCavity-altered superconductivity - Nature

A grand aspiration of cavity quantum materials research is to uncover fundamentally new routes for controlling properties of matter by judiciously tailoring the quantum electromagnetic environment. Experiments with dark cavities revealed modified transport properties in the integer and fractional quantum Hall states of a 2D electron gas, as well as cavity-assisted thermal control of the metal-to-insulator transition in charge-density-wave systems.

Science

[ Load more ]