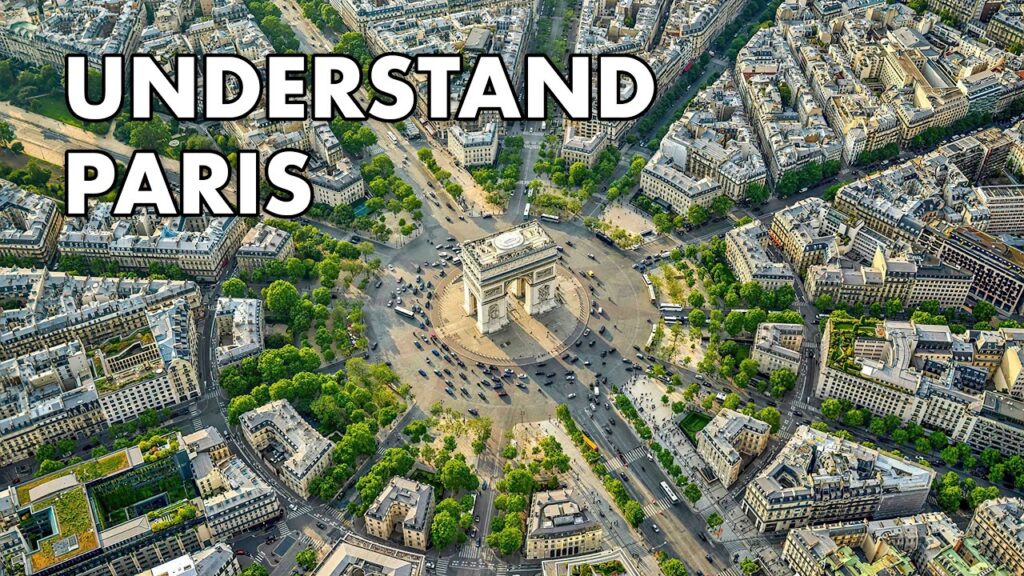

"Even today, the Paris of the pop­u­lar imag­i­na­tion is, for the most part, the Paris envi­sioned by Baron Georges-Eugène Hauss­mann and made a real­i­ty in the eigh­teen-fifties and six­ties. Not that he could order the city built whole: as explained by Manuel Bra­vo in the new video above, Paris had already exist­ed for about two mil­len­nia, grow­ing larg­er, denser, and more intri­cate all the while. But as the pre­fect under Emper­or Napoleon III, Hauss­mann was empow­ered to carve it up by force, open­ing "dozens of wide, long avenues that con­nect­ed impor­tant parts of the city," a lay­out that "mir­rored the street sys­tem in Rome cre­at­ed 300 years ear­li­er by Pope Six­tus V, but on a much grander scale.""

"How­ev­er con­sid­er­able the vio­lence it did to medieval Paris, this process of " Hauss­m­an­niza­tion" showed a cer­tain his­tor­i­cal con­scious­ness. After all, the French cap­i­tal was once a Roman city: Lute­tia Pariso­rum, named for the Parisii, the Gal­lic tribe that had inhab­it­ed the island in the mid­dle of the Seine that Parisians now call Île de la Cité."

"As was their usu­al modus operan­di, the con­quer­ing Romans laid a car­do max­imus run­ning from north to south, today known as Rue Saint-Jacques. There­after, "the rest of the orig­i­nal lay­out was lost to organ­ic growth." In the form Paris even­tu­al­ly took in the Mid­dle Ages, "there were no pub­lic urban spaces of major sig­nif­i­cance": no Place Dauphine, no Place des Vos­ges, no Place Vendôme."

Paris’s modern appearance largely results from the mid-nineteenth-century restructuring led by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, which inserted broad, long avenues and formal public spaces into an older, denser city. Paris originated as the Roman Lutetia Parisiorum, with a north–south cardo now Rue Saint-Jacques, but medieval organic growth obscured the original layout. Medieval Paris lacked major public urban squares. Haussmann’s interventions both erased and referenced earlier layers, creating a grander axial plan that mirrored Roman precedents while dramatically altering the medieval urban fabric.

Read at Open Culture

Unable to calculate read time

Collection

[

|

...

]