fromwww.mediaite.com

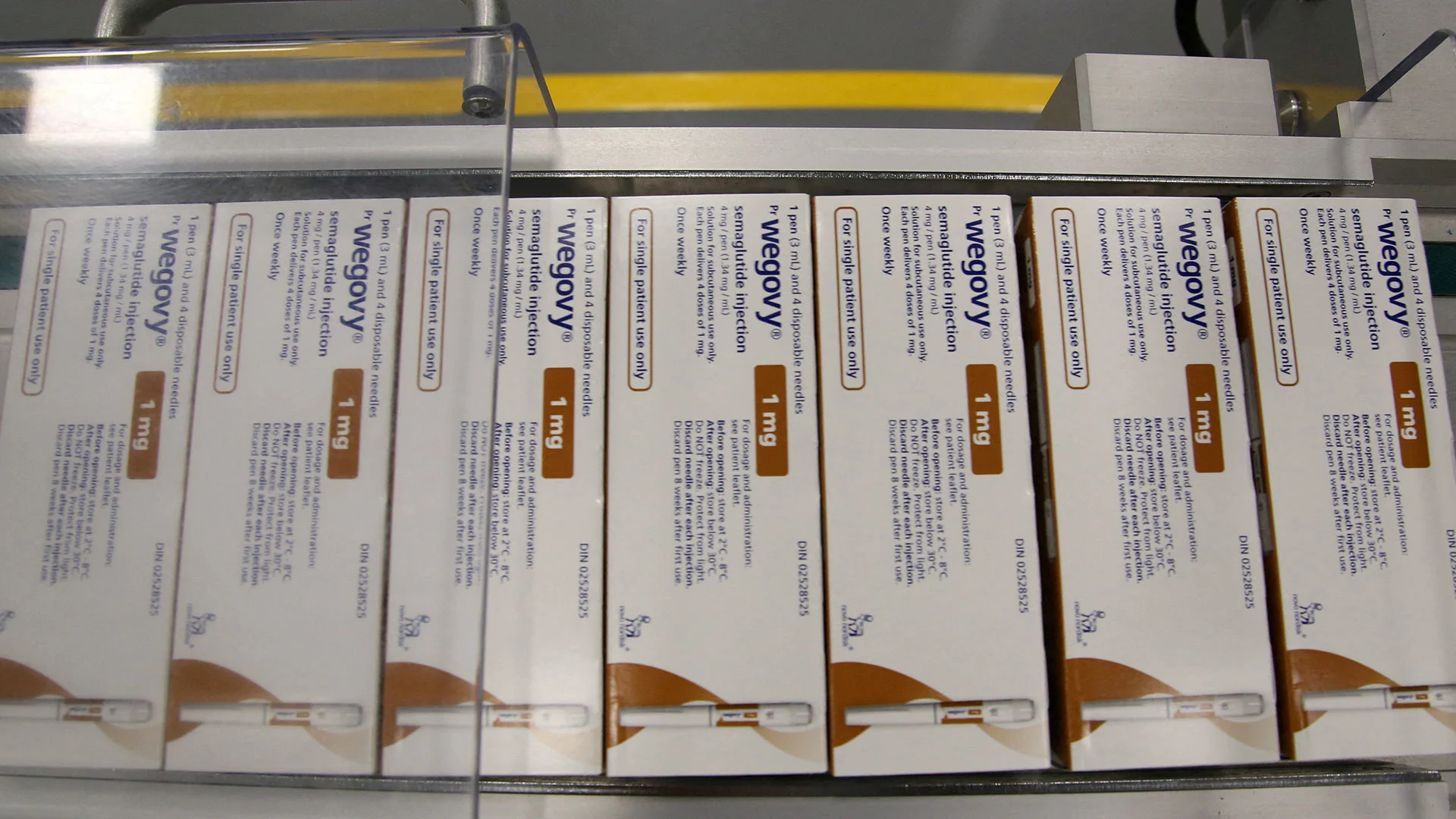

1 week agoReporter Asks JB Pritzker if He Decided to Lose Weight Because He Might Run for President

I don't know about other people. I've been challenged with my weight for, you know, most of my life so the idea and I have succeeded and failed, I mean, like a lot people, you lose weight, you gain weight over the course of your life. I realize that other people want to make this about something that it's not, the governor said.

US politics