"The pelvis is often called the keystone of upright locomotion. More than any other part of our lower body, it has been radically altered over millions of years, allowing our ancestors to become the bipeds who trekked and settled across the planet. But just how evolution accomplished this extreme makeover has remained a mystery. Now a new study in the journal Nature led by Harvard scientists reveals two key genetic changes that remodeled the pelvis and enabled our bizarre habit of walking on two legs."

""What we've done here is demonstrate that in human evolution there was a complete mechanistic shift," said Terence Capellini, professor and chair of the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology and senior author of the paper. "There's no parallel to that in other primates. The evolution of novelty - the transition from fins to limbs or the development of bat wings from fingers - often involves massive shifts in how developmental growth occurs. Here we see humans are doing the same thing, but for their pelves.""

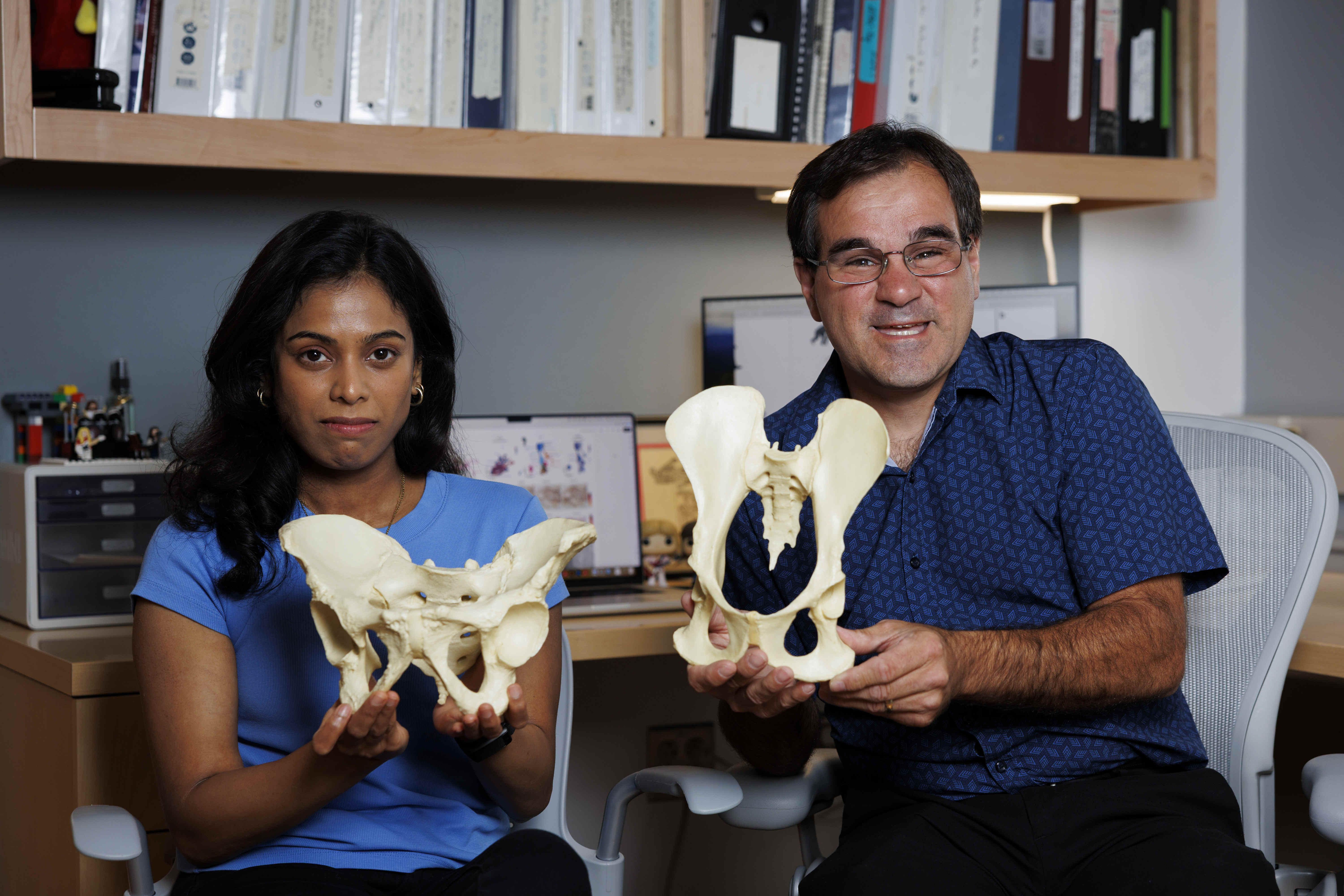

"Anatomists have long known that the human pelvis is unique among primates. The upper hipbones, or ilia, of chimpanzees, bonobos, and gorillas - our closest relatives - are tall, narrow, and oriented flat front to back. From the side they look like thin blades. The geometry of the ape pelvis anchors large muscles for climbing. In humans, the hipbones have rotated to the sides to form a bowl shape (in fact, the word "pelvis" derives from the Latin word for basin)."

Two key genetic and developmental changes remodeled the hominin pelvis and enabled habitual bipedal walking. Human iliac blades rotated laterally to form a bowl-shaped pelvis, providing flaring hipbones that anchor muscles for balance during single-leg stance and locomotion. Ape ilia remain tall, narrow, and oriented front-to-back, suited for climbing. The pelvic transformation involved a mechanistic shift in developmental growth patterns, analogous to major evolutionary novelties such as the transition from fins to limbs. These changes altered pelvic geometry and muscle attachments, facilitating efficient weight transfer, balance, and endurance running in upright hominins.

Read at Harvard Gazette

Unable to calculate read time

Collection

[

|

...

]