#quantum-mechanics

#quantum-mechanics

[ follow ]

#physics #time #general-relativity #cosmology #parallel-universes #quantum-technology #theoretical-physics

Science

fromwww.scientificamerican.com

1 week agoThe Schrodinger equation is getting a glow-up for its 100th birthday

Including observers within the Schrodinger equation reveals new perspectives and may redefine boundaries of quantum mechanics, addressing enduring mysteries about measurement and reality.

fromBig Think

1 month agoDoes our physical reality exist in an objective manner?

Although there are always some philosophical assumptions behind this conclusion, it's an assumption that isn't contradicted by anything we've ever measured under any conditions: not with human senses, not with laboratory equipment, not with telescopes or observatories, not under the influence of nature alone nor with specific human intervention. Reality exists, and our scientific description of that reality came about precisely because those measurements, conducted anywhere or at any time, is consistent with that very description of reality itself.

philosophy

Science

fromwww.scientificamerican.com

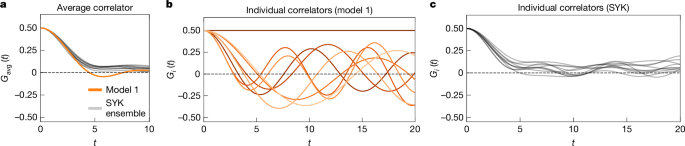

4 months agoQuantum Tunneling Is a Big Deal. This Year's Nobel Physics Prize Shows Why

Macroscopic electronic circuits can exhibit collective quantum tunneling, demonstrating that quantum mechanics applies at visible scales and enabling quantum electrical engineering.

fromwww.theguardian.com

4 months agoNobel prize in physics awarded to three scientists for work on quantum mechanics

The Nobel prize in physics 2025 has been awarded to British, French and American scientists for their work on quantum mechanics. John Clarke, a British physicist based at the University of California at Berkeley, Michel Devoret, a French physicist based at Yale University, and John Martinis, of the University of California Santa Barbara, share the 11m Swedish kronor (about 871,400) prize announced by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm.

Science

fromNature

5 months agoEinstein hated entanglement - and five other quantum myths

Quantum mechanics is unquestionably a robust and successful theory - so far, all its predictions have held, and scientists can build powerful technologies based on it. Yet, understanding what it tells us about the nature of reality and how we experience it has proven tricky. Physicists and philosophers have been grappling with it for a century, ironing out some of the early ambiguities, but some conceptual problems remain.

Science

[ Load more ]