#pandemic-preparedness

#pandemic-preparedness

[ follow ]

#public-health #global-health #vaccination #vaccine-development #health-security #bird-flu #misinformation

Artificial intelligence

fromFortune

1 month agoBill Gates says AI could be used as a bioterrorism weapon akin to the COVID pandemic if it falls into the wrong hands | Fortune

Artificial intelligence will change society more than past inventions and poses significant benefits and risks, including bioterrorism and job disruption.

fromwww.aljazeera.com

1 month agoGlobal health's defining test

Perhaps the most significant milestone was the adoption by WHO Member States of the Pandemic Agreement, a landmark step towards making the world safer from future pandemics. Alongside this, amendments to the International Health Regulations came into force, including a new pandemic emergency alert level designed to trigger stronger global cooperation. And to sustainably finance the WHO's work, governments in a historic show of support increased their contributions to our core budget.

Public health

fromHarvard Gazette

2 months agoStopping the next pandemic - Harvard Gazette

A team of researchers from the Broad Institute and Harvard began to suspect nearly two decades ago that so-called "emerging diseases" such as Ebola and Lassa virus were not quite what they seemed. Rather than being newly evolved contagions, mounting evidence suggested they were ancient pathogens that had circulated among humans for thousands of years. What really was emerging was accurate diagnosis: Medicine only recently had acquired the ability to detect these diseases and track the toll of outbreaks.

Science

fromThe Atlantic

3 months agoTo Survive the Next Pandemic, Walk More, the NIH Says

The standard pandemic-preparedness playbook "has failed catastrophically," NIH Director Jay Bhattacharya and NIH Principal Deputy Director Matthew J. Memoli wrote in City Journal, a magazine and website published by the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, a conservative think tank. The pair argue that finding and studying pathogens that could cause outbreaks, then stockpiling vaccines against them, is a waste of money.

Public health

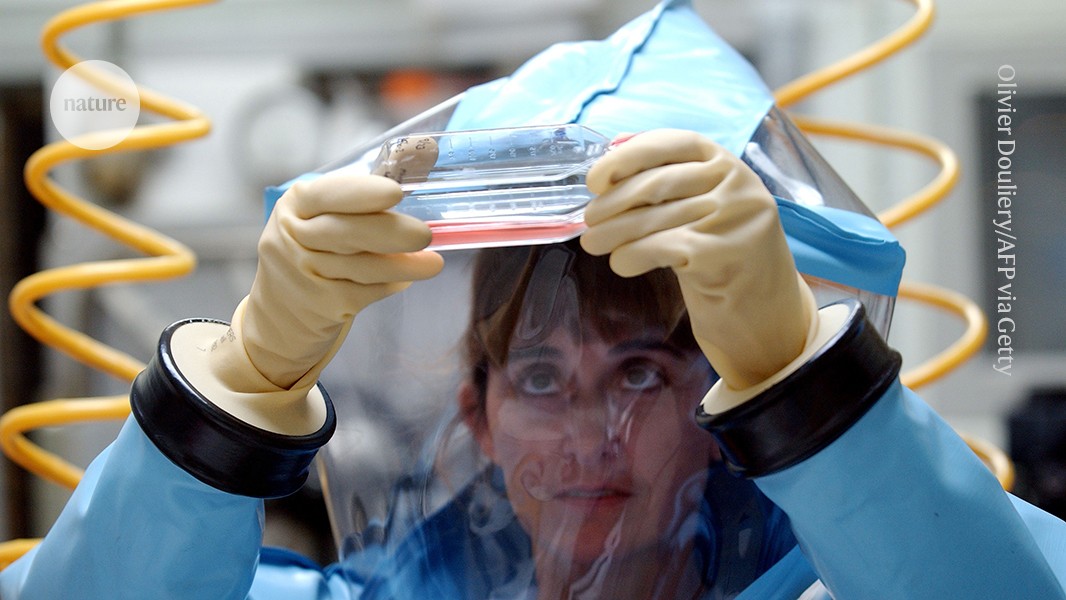

fromNature

3 months agoHow COVAX raced to protect the world from COVID-19

Most people don't like getting vaccines, much less seeing their children have needles poked into their thighs and arms. But context can change that. Besieged by terrifying outbreaks of paralytic polio and the spectre of iron-lung respirators, many parents were happy to see their children receiving the first polio vaccinations in the 1950s. Similarly, when I got my first COVID-19 vaccine, it instantly relieved the sense of existential dread that I had felt for almost a year as the death toll rose.

Public health

#public-health

Coronavirus

fromMedCity News

8 months agoIn Axing mRNA Contract, Trump Delivers Another Blow to US Biosecurity, Former Officials Say - MedCity News

The Trump administration's contract cancellation threatens U.S. pandemic preparedness and national defense, making Americans vulnerable to potential biological threats.

fromwww.npr.org

7 months agoCanceled grants get the spotlight at a Capitol Hill 'science fair'

These discoveries may not just save our own lives, but the lives of people we love. Nearly every innovation that defines our era, every breakthrough from my field and from those of my colleagues, traces back to basic science research.

US news

European startups

fromSilicon Canals

9 months agoDutch-based Leyden Labs secures 20M from EIB

Leyden Laboratories secures €20M funding to enhance pandemic preparedness through innovative antiviral research.

The focus is on developing non-vaccine therapies for respiratory viruses, specifically a nasal spray targeting influenza.

fromwww.scientificamerican.com

10 months agoUniversal Vaccines Have Eluded Scientists for Years. RFK, Jr., Is Betting This Approach Will Succeed

Scientists have pursued a universal influenza vaccine for decades to protect against various strains, with recent plans for $500 million in funding marking significant progress.

Coronavirus

[ Load more ]