Mental health

fromNature

1 week agoDaily briefing: What people with no 'mind's eye' can tell us about consciousness

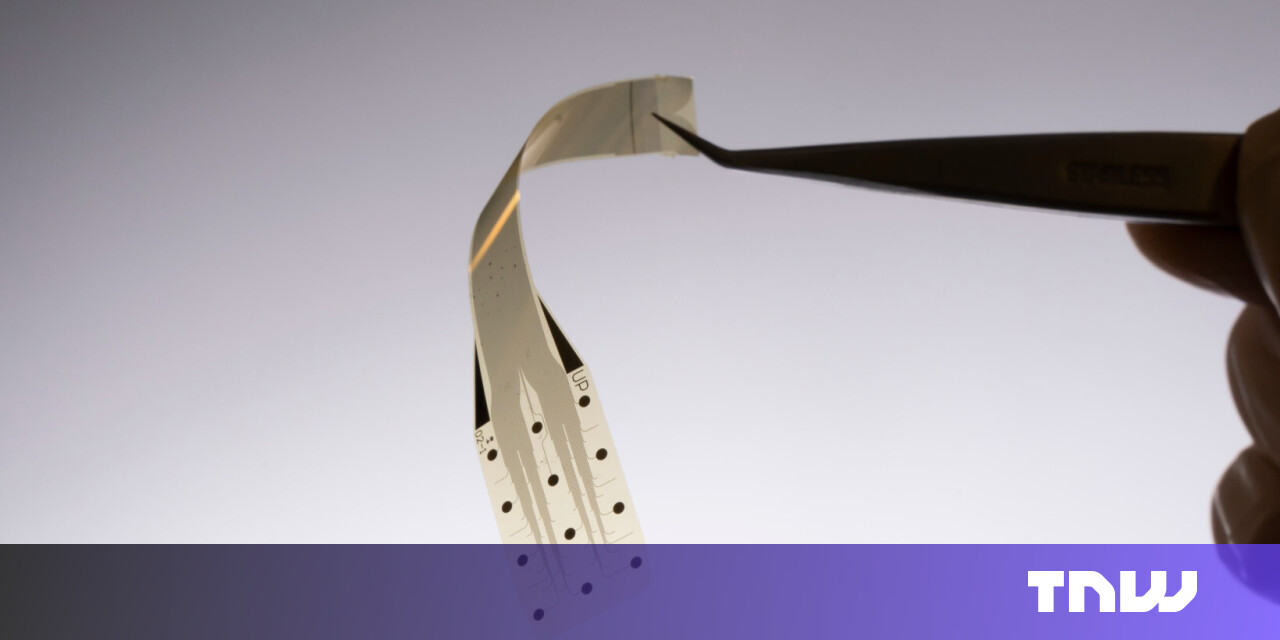

Vividness of mental imagery, handwriting practices, psychiatric-diagnostic revisions, and emerging brain–computer interfaces shape memory, creativity, education, mental-health classification, and technology development.