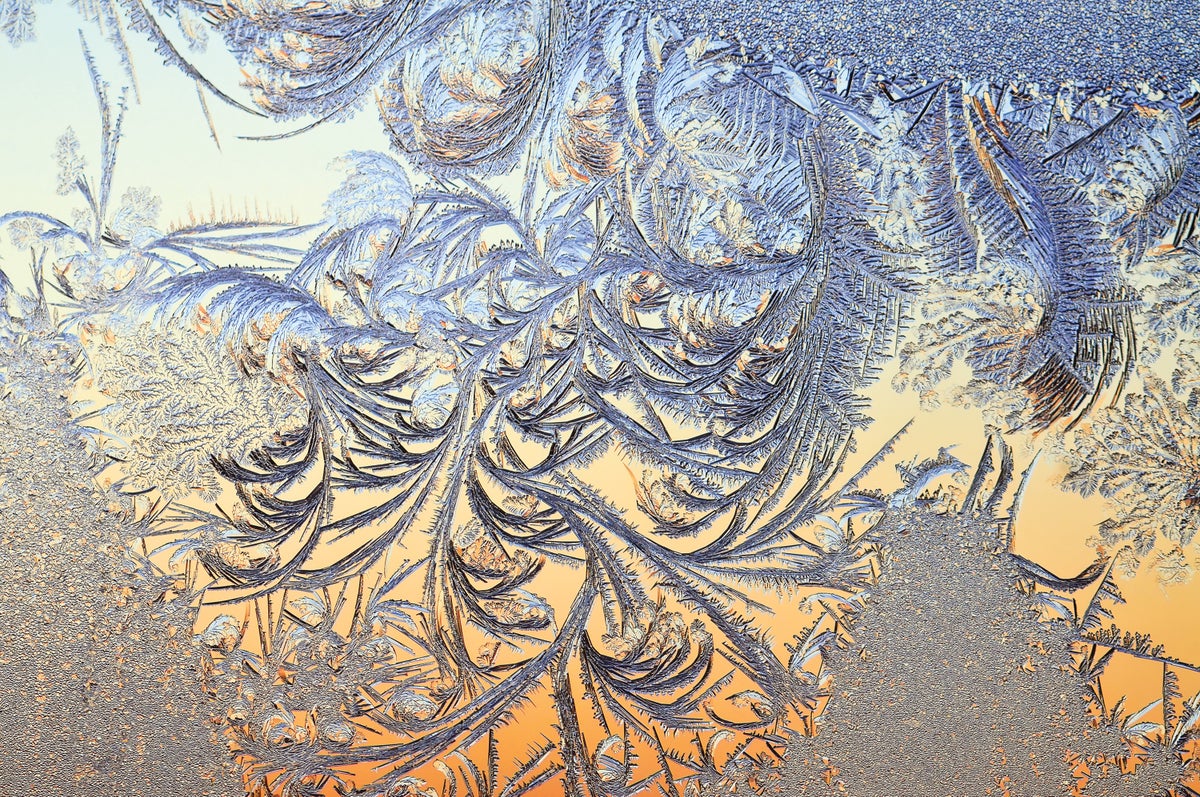

"Chances are that all your encounters with frozen waterwhile trudging through slushy winter streets, perhaps, or treating yourself to cool summer lemonadeshave been confined to one structural form of ice, dubbed Ih, with the h referring to its crystal lattice's hexagonal nature. But there is so much more to ice than that. For more than a century scientists have been striving to push ice into extreme conditions, creating progressively more exotic structuresthey've made more than 20 crystalline forms to date, in fact, none of which we are likely to experience in our lifetimes."

"At the heart of all these exotic icesand our more mundane ice, as well as water and steamis the same molecule: H2O, an oxygen atom flanked by hydrogen atoms forming an angle of 104.5 degrees. In every variety of ice, H2O molecules interact, with weak connections called hydrogen bonds forming between one oxygen and one hydrogen atom in separate molecules. Different arrangements of these hydrogen bonds can shape ice's crystalline structure into various configurations, from a hexagonal prism to a cubic lattice to less familiar lattice systems such as rhombohedral and tetragonal."

Everyday frozen water most often appears as the hexagonal crystal Ih. Scientists have synthesized more than 20 distinct crystalline ice phases under extreme temperature and pressure conditions. All forms of ice, and liquid water and steam, consist of H2O molecules with an oxygen atom bonded to two hydrogens at a 104.5° angle. Hydrogen bonds between an oxygen and a hydrogen on different molecules determine crystalline arrangement. Variations in hydrogen-bond patterns produce lattice systems such as hexagonal, cubic, rhombohedral, and tetragonal. Hydrogen bonds are highly sensitive to temperature and pressure, producing dramatic, sometimes quantumlike, changes in molecular relationships.

Read at www.scientificamerican.com

Unable to calculate read time

Collection

[

|

...

]