"The study refutes foundational knowledge in the field of neuroscience that losing a limb results in a drastic reorganization of this region, the authors say. Pretty much every neuroscientist has learnt through their textbook that the brain has the capacity for reorganization, and this is demonstrated through studies on amputees, says study senior author Tamar Makin, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Cambridge, UK. But textbooks can be wrong, she adds. We shouldn't take anything for granted, especially when it comes to brain research."

"But the latest findings, published in Nature Neuroscience on 21 August, reveal that the primary somatosensory cortex stays remarkably constant even years after arm amputation. The discovery could lead to the development of better prosthetic devices, or improved treatments for pain in phantom limbs' when people continue to sense the amputated limb. It could also help scientists working to restore sensation in people who have had amputations."

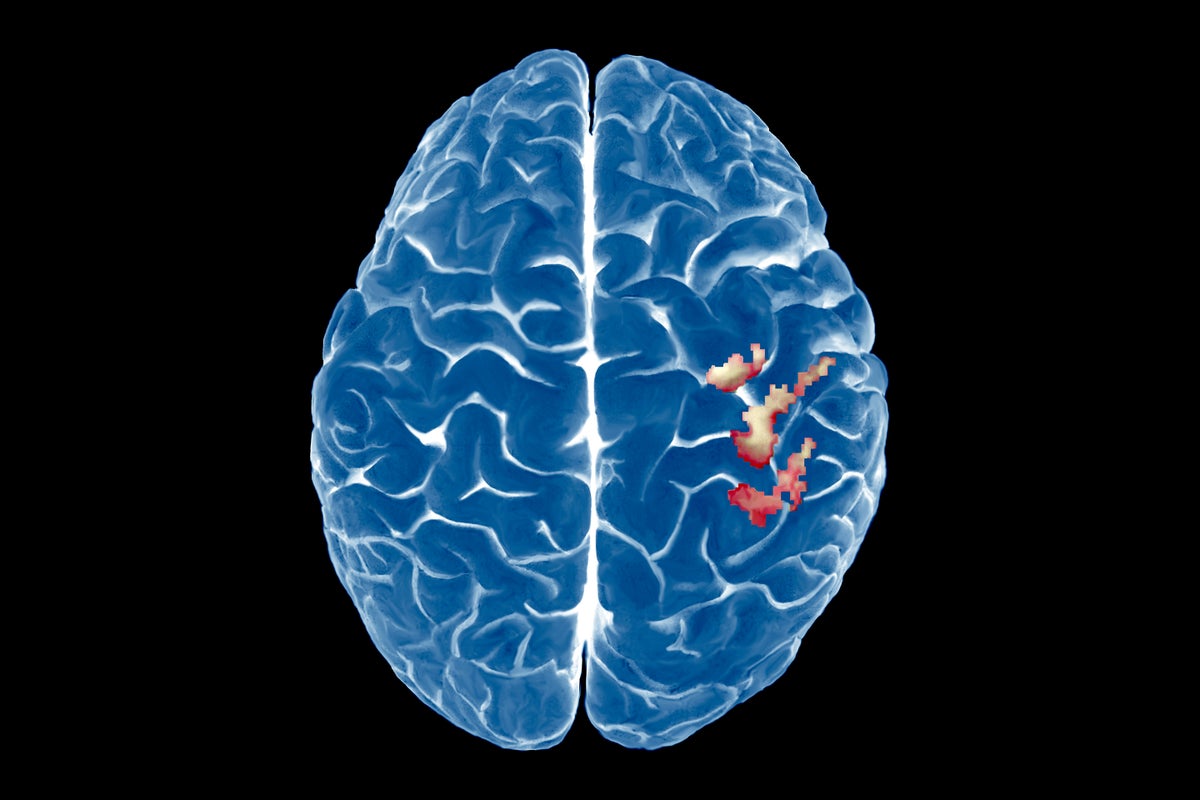

Brain imaging of people with amputated arms reveals that the primary somatosensory cortex remains remarkably constant even years after amputation, contradicting the long-standing belief that losing a limb causes large-scale cortical reorganization. Previous models proposed that neurons from adjacent cortical areas would invade the region that previously represented the missing limb. The observed stability of somatosensory maps implies limited remapping after limb loss and calls for revisiting textbook accounts of cortical plasticity. Practical implications include potential improvements in prosthetic devices, better treatments for phantom limb pain, and refined approaches to restoring sensation in amputees.

Read at www.nature.com

Unable to calculate read time

Collection

[

|

...

]