"Art heists always capture the imagination-just ask officials at the Musée du Louvre-and the theft of a Rembrandt in 1975 was no exception. On 14 April 1975, Myles Connor entered the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston in disguise along with an accomplice. The pair went directly to the Dutch Gallery and proceeded to remove Rembrandt's Portrait of Elsbeth van Rijn from the wall."

"In his new book, Anthony Amore delves into Connor's life and adventures as an art thief, outlining why the Rembrandt robbery mattered. As well as being an author, since 2005 Amore has been the director of security and the chief investigator at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston-the site of one of the most renowned unsolved art thefts in 1990, when 13 works, including pieces by Rembrandt, Johannes Vermeer and Edgar Degas, were stolen."

"While the inspiration behind nearly every art heist is money, Connor's motivations were unusual. For instance, he once robbed a museum of dozens of pieces from its collection because they had insulted his father. And the titular heist was not because he hoped to sell or enjoy the Rembrandt painting itself. Rather, he wanted only to borrow it for a while. So while contemporary investigators can start with certain assumptions about major heists, they must not ignore possibilities that do not fit a profile."

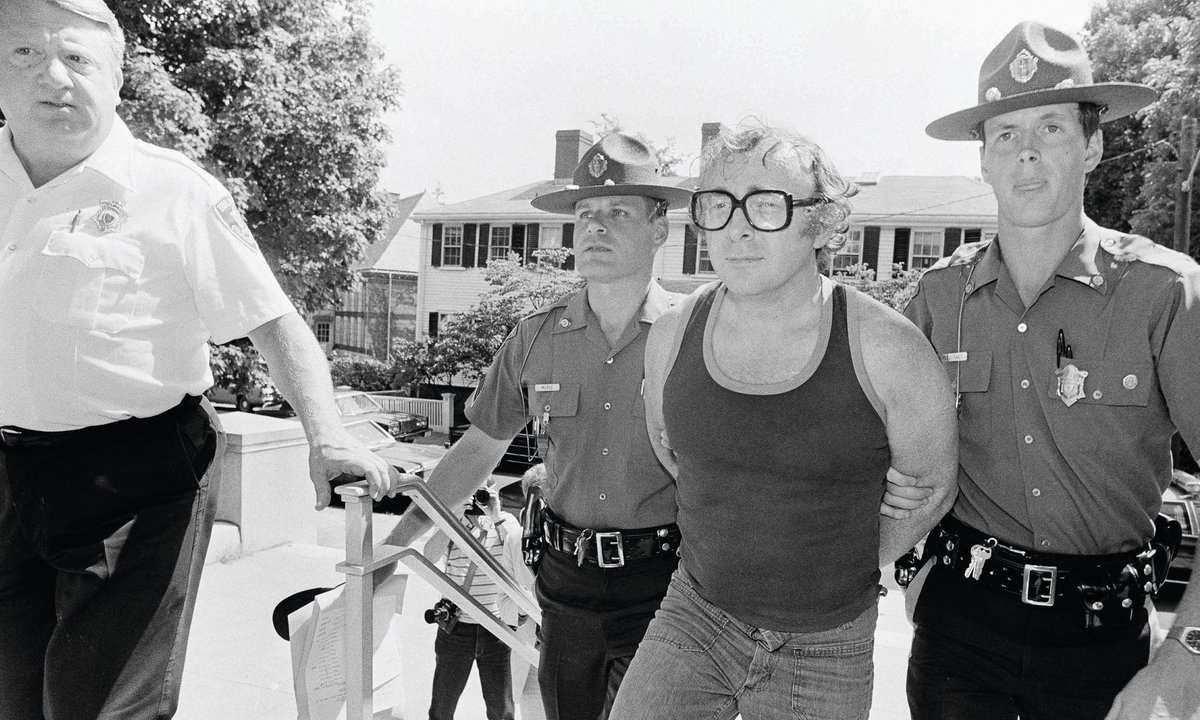

Myles Connor entered the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston in disguise on 14 April 1975 with an accomplice and removed Rembrandt's Portrait of Elsbeth van Rijn from the Dutch Gallery. Connor was an experienced career criminal who later used the Rembrandt as leverage to obtain stolen works by Andrew and N.C. Wyeth. Connor's motives were often atypical: he once stole dozens of pieces because a museum insulted his father and he intended to borrow, not sell, the Rembrandt. People who steal high-value art are often common criminals rather than specialists, and museums present attractive targets due to unique items and security gaps. Investigators must avoid narrow profiling and consider unconventional motives.

Read at The Art Newspaper - International art news and events

Unable to calculate read time

Collection

[

|

...

]