"The neoclassical sculptor and draughtsman Johan Tobias Sergel is a household name in his native Sweden, but little known elsewhere. This month Swedes will get a grand overview of Sergel's work for the first time in a generation, when Stockholm's Nationalmuseum mounts Fantasy and Reality, with a checklist of close to 400 works. Then in the autumn, Americans will get an introduction to the artist when New York's Morgan Library & Museum hosts Sergel's first monographic show in the US."

"Sergel (1740-1814) lived a productive and eventful life that took him from artistic circles in 1770s Rome to the late 18th-century court of his patron, the Swedish King Gustav III. Nominally an early and influential neoclassical figure, he was also marked by Sweden's love affair with the Rococo and, some scholars argue, by a proto-Romantic sensibility shared with his Rome buddy, the Swiss artist Henry Fuseli."

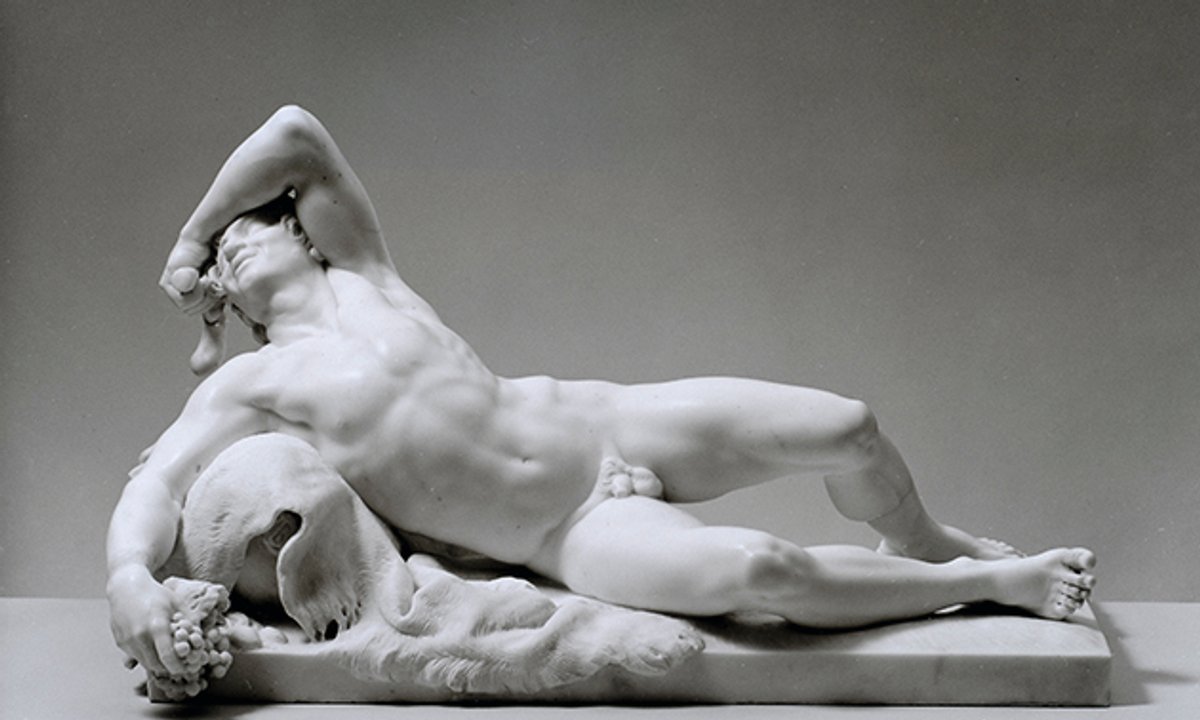

"Sergel's Cupid and Psyche (1787) captures the god's early rejection of the beautiful woman who would become his wife. The artist's earliest sketches for the work, set for display, "show how he wanted to catch this specific moment", says Prytz, who thinks the final statue is more compelling than a different and more famous depiction of the two figures by Antonio Canova."

Stockholm's Nationalmuseum mounts Fantasy and Reality, presenting nearly 400 works by Johan Tobias Sergel, and New York's Morgan Library & Museum stages Sergel's first US monographic show. Sergel (1740-1814) moved from artistic circles in 1770s Rome to the court of King Gustav III, blending neoclassical principles with Swedish Rococo tastes and a proto‑Romantic sensibility linked to Henry Fuseli. The Nationalmuseum holds most of his output, including massive marble sculptures and more than 200 fragile drawings requiring conservation and careful transport. Cupid and Psyche (1787) captures the god's early rejection; the final statue is judged more compelling than Antonio Canova's rendition. Both exhibitions examine Sergel's Roman artist network through international loans.

Read at The Art Newspaper - International art news and events

Unable to calculate read time

Collection

[

|

...

]