fromPitchfork

6 days agoPeter Gabriel Lines Up a New Year of Lunar Releases With O/I

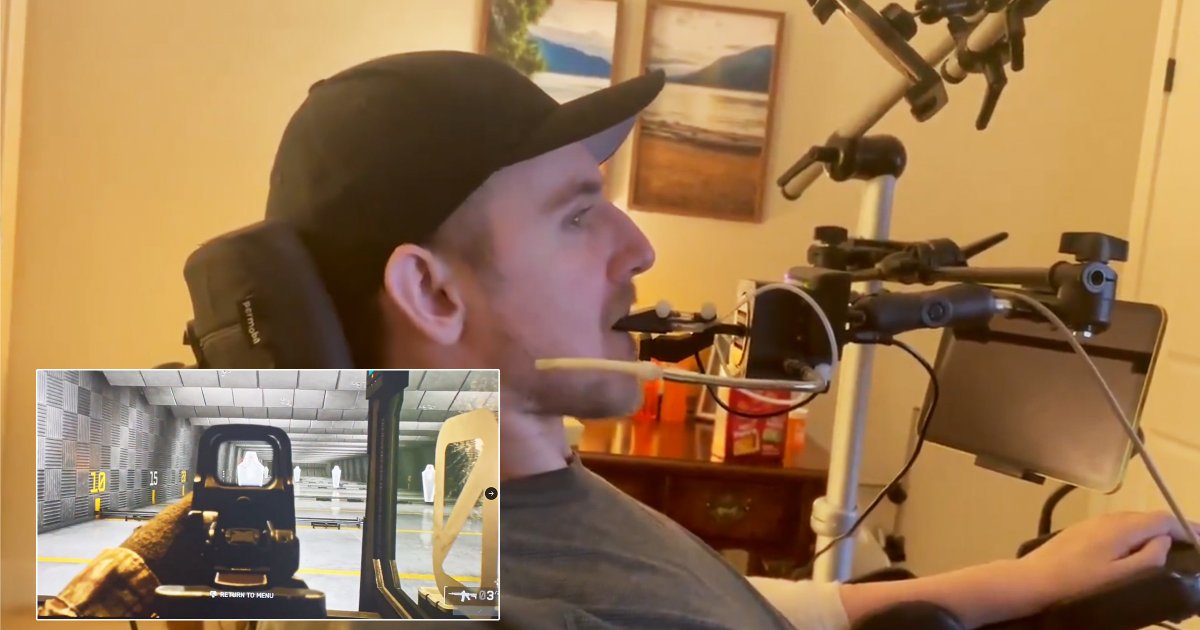

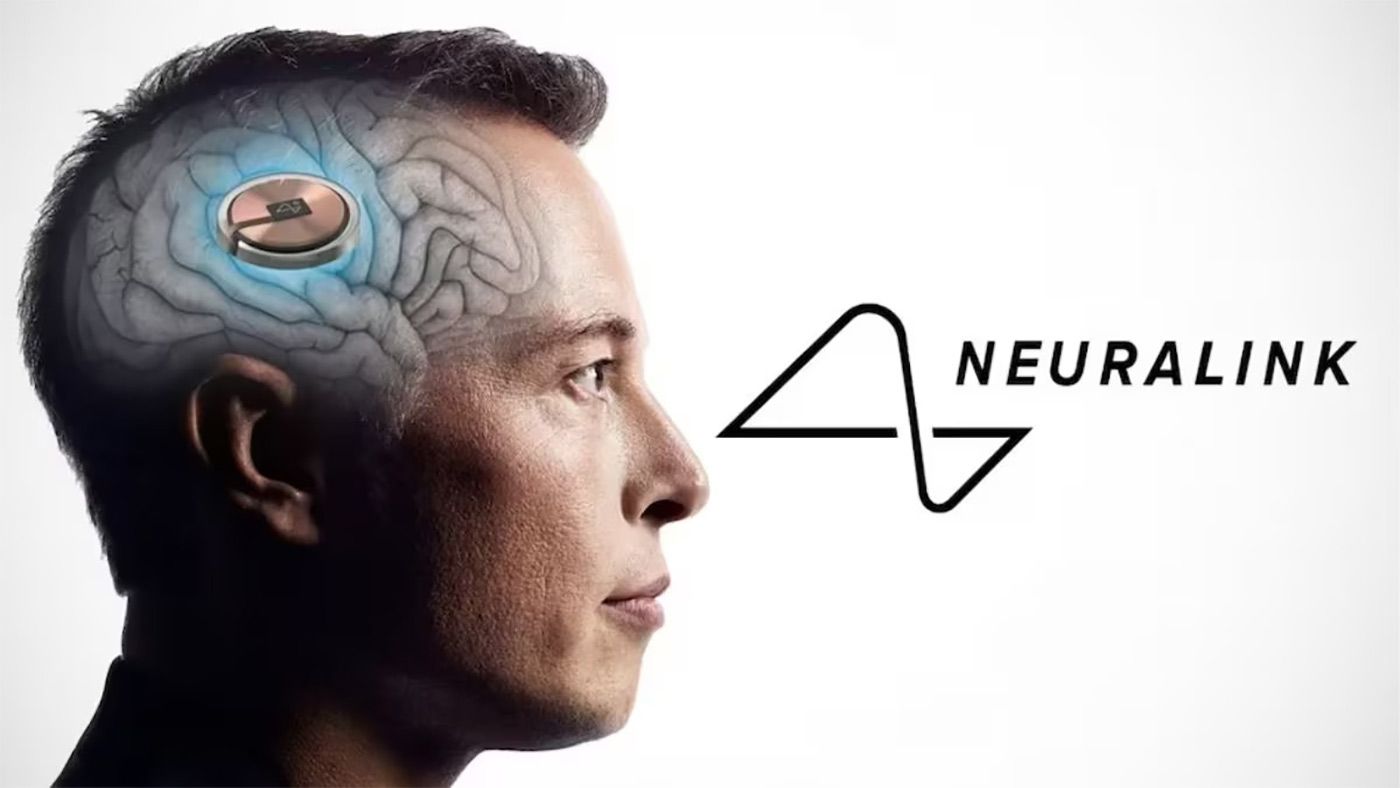

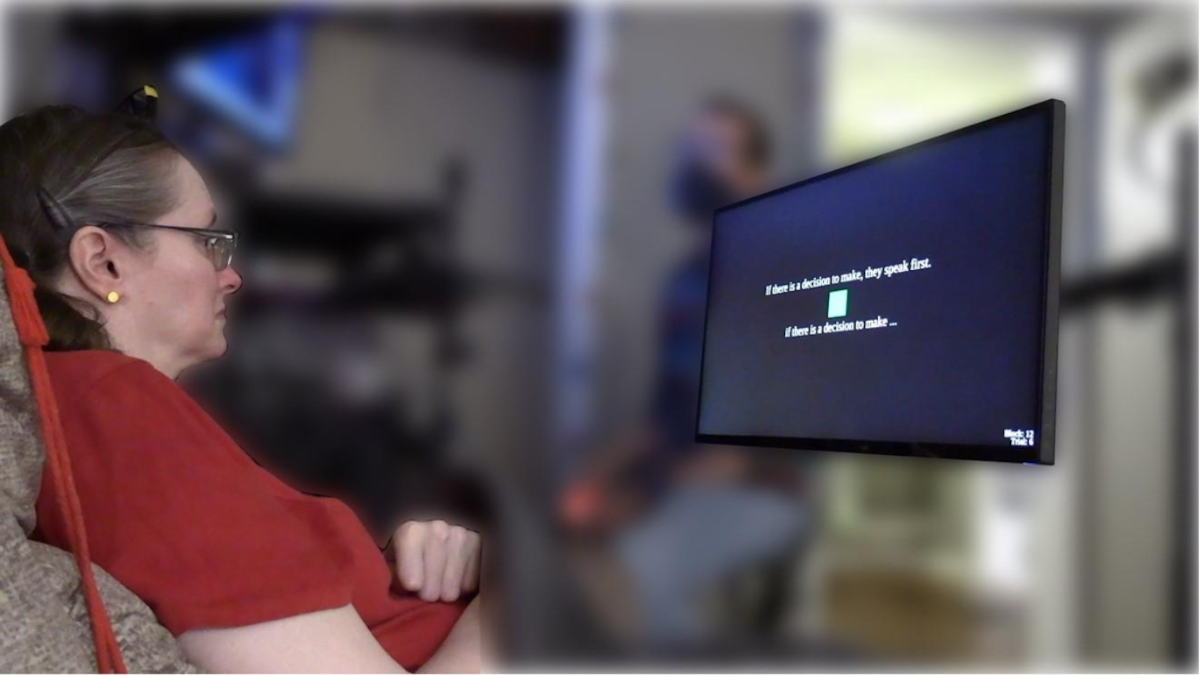

I have been thinking about the future and how we might respond to it. We are sliding into a period of transition like no other, most likely triggered in three waves; AI, quantum computing and the brain computer interface. Artists have a role to look into the mists and, when they catch sight of something, to hold up a mirror.

Music